- Home

- A W Hartoin

The Wife of Riley (Mercy Watts Mysteries Book 6) Page 13

The Wife of Riley (Mercy Watts Mysteries Book 6) Read online

Page 13

“Yes. Let’s bet. Ten bucks says you can’t be with me every second.”

He hugged the breath out of me again. “You know what I mean.”

“I do, but it’s pointless to try.”

We walked home hand in hand. Chuck wouldn’t say anything else about the bathroom incident and I forced myself not to push. Not an easy thing given my lineage. I wondered what Mom would’ve done in my place. The right thing, undoubtedly. Whatever that was.

My thoughts strayed to Angela Riley. I was getting closer. If she really was in Paris, could she feel me closing in or would I come as a surprise? I supposed it didn’t matter. I was coming. I’d had a taste of success and I wouldn’t give up and Calpurnia expected nothing less. Six days left in Paris. Sabine was off my list and it was on to the Orsay. Time to call in a favor.

Chapter Thirteen

The favor was easy to obtain, even at midnight. I called Myrtle and Millicent’s connection at the Orsay, Monsieur Dombey. I knew from what The Girls said that Monsieur Dombey would just be getting home from dinner and drinks. He was wide awake and remembered me from our previous visits. I asked to be allowed into the museum before opening and he said he’d be honored to accommodate a Bled. That’s what he called me, a Bled. I didn’t correct him and I felt a little bad about that. I wasn’t a Bled and I didn’t usually let that mistake stand. I did need to get into the Orsay early to position myself for my next target, so I let it go with a silent apology for my impersonation.

Chuck and I walked up the wide stones to the Musée d’Orsay entrance with Aaron lagging behind, muttering about duck fat. He’d gotten up at five to roast a Brest chicken and potatoes in duck fat. The results weren’t to his liking, but I had no clue why. Tasted great to me, although I think I could hear my arteries hardening as we walked. He was so fussy, I thought we were going to be late and that would be a faux pas, to say the least. Monsieur Dombey was never ever late and he wasn’t that morning. We cleared the last step and found him standing beside the queueing maze outside the Orsay’s main entrance. Monsieur Dombey spotted us and clapped his hands before hurrying over.

“He’s young,” said Chuck with astonishment.

“What were you expecting?” I asked.

“Well…I guess Mr. Burns from The Simpsons.”

“Why in the world—”

Monsieur Dombey held out his big hands to me. “Mademoiselle Watts, it is my pleasure to see you.”

We gave each other cheek kisses like old friends, which I guess we were. I met Serge Dombey years ago when I was thirteen and he was twenty-one, fresh out of the Sorbonne and adorably terrified at being ordered to accompany Bleds around the museum. The Girls made it easy on him with their charming ways and genuine love of art. I had a huge crush on Serge. He wasn’t like any other Frenchman I’d met, big and bulky with the hands of a farmhand, not a painter, which was what he was in his off-duty time.

“Please,” I said. “Call me Mercy.”

“And you must call me Serge.”

It took us five minutes to go through the dance of politeness that was required given our respective positions. When we agreed that it was acceptable to call each other by our first names, I introduced Chuck and Aaron. They would be called by their formal titles. No way around it. They hadn’t known Serge for ten years.

“Right this way,” said Serge with an arm sweep toward the reserved entrance.

“Where is everyone?” asked Chuck.

“I told you we’re getting a special tour because of The Girls,” I said as we went through the doors and past ticketing.

“This is pretty special.”

Pretty special didn’t cover it. The Girls were VIPs. The Bleds had a relationship with the Orsay since its inception. They’d been huge supporters of the idea of turning the train station into a museum and donated generously. The Orsay was the only museum in the world that they loaned pieces to and it was all because of Elias Bled. Few outside the family knew about him. Elias was that kind of secret.

The Bleds, while being geniuses at business and brewing, also had a streak of insanity running through the family. Elias had been one of those. Born in the mid-1800s, he fancied himself a painter. No one knew how he got that idea, since he couldn’t draw a stick. The family tried to convince him that he was better at business, but he knew better. He moved to Paris and bought an apartment on the Île Saint-Louis. There, he created terrible paintings and even worse sculptures, but he became friends with the soon to be great artists of the day, Pissarro, Monet, and many more. Elias had no end of money and he supported many of the artists by commissioning works. All the work he’d purchased was found in his apartment after he’d been missing for a couple of weeks. Elias’s close friend, the artist Jean-François Raffaëlli, telegrammed the family saying he couldn’t find Elias. There was something about a woman, possibly a prostitute, that Elias had fallen in love with. Whoever this woman was, she ran off and Elias was distraught. Several friends saw him on the Pont Marie near his apartment, gazing into the water. Elias’s brother, Constantine Bled, was dispatched to Paris to find Elias, but he never turned up. The art community supported the family and the search and the Bleds always felt a special connection to the art and artists of the period.

The Orsay never tried to dictate to the Bleds. Other museums did, trying to say that they must do this or that for the good of the public. The Orsay knew how to handle the rich and eccentric better than anyone else in the art world and they were rewarded for it. The Bleds didn’t even want credit for what they did for the museum. The works they loaned weren’t attributed to them, neither was the influx of cash that came every so often. The Orsay loved the Bleds and consequentially me.

“Can I get you anything before we start?” asked Serge, ready to make us coffee with his own hands, if necessary.

“I think we’re fine,” I said. “Thank you.”

“Would you like to begin at the beginning?”

Chuck grinned. “Is there a better place?”

“Not in my opinion. Shall we?” Serge led us into the main gallery. The glass arched ceiling made everything feel light and airy. The grand hall’s creamy stone set off the sculptures, making them seem small until you were standing next to them.

“Nice,” said Chuck, his head swiveling like crazy.

“We’ll start with early Romanticism and go through all the periods,” said Serge. Chuck got a little stony-faced at the idea of multiple periods, but Serge knew his business. He said just the right amount for me, someone who’d seen it all before, and for Chuck, whose interest in art was in its infancy. We saw Monet, Gauguin, and Toulouse-Lautrec. Chuck blushed at The Origin of the World. Aaron didn’t blush or appear to think anything was remotely interesting about the work that shocked pretty much everybody who saw it for the first time. He stood in front of that famous crotch and asked, “You hungry?”

Serge raised an eyebrow and I gave him a little eye roll. Aaron was weird. He might as well know it. I glanced at my watch and at the museum staff starting to arrive. We had an hour left before opening and Corrine Sweet, my next possibility, would be in the bookshop.

“Not yet,” I said. “Let’s finish the tour.”

We worked our way through the rest and I could see Chuck starting to sag. Art did wear people out, even with an excellent guide like Serge. The clock on the top re-energized him. There’s nothing like that clock to make a person feel separate from Paris yet a part of something special at the same time. The face was clear with black Roman numerals and hands. Chuck and I posed for a picture, careful not to obscure Sacré-Coeur in the distance, its white domes gleaming in the morning sun.

We toured the main Impressionists gallery and I fell in love with the faces once again. Renoir’s veil over Mme. Paul Darras’s face entranced me as always. How did he do that? The faces didn’t do it for Chuck. He bypassed the sunny scenes of luscious ladies topless in fields and went right to the winter scenes of the sea or icy villages encased in thick snow.

“You like

Sisley?” I asked.

“Who?”

“Alfred Sisley, the artist.”

He stared at a figure walking down a lane between two snow-covered walls to what looked like a dead end. “It’s very…”

“Lonely,” I suggested, taking his hand.

“You think so?” he asked.

“I prefer the sun.”

He kissed my forehead and chuckled. “Of course you do.”

Serge had been allowing us to explore on our own, interjecting tidbits now and again. He always did have perfect timing. “Several of the artists enjoyed the winter. Monet was often observed, half-frozen, studying the constantly changing appearance of snow. Perhaps you will like The Magpie as well.”

Chuck did like The Magpie and every other chilly work he showed him. I strayed to the faces of people long dead and wondered about them. Did they know or have the smallest hint that a great artist had captured them for all time and they would someday be seen by millions and admired? I supposed a woman sipping absinthe in a café couldn’t possibly know what Degas would do with her ordinary face. Still, I wondered.

We finished the Impressionists and headed to the room installations of Art Nouveau furniture and Aaron said, “You hungry?”

“Yes,” I said. “And I think we’ve seen it all.”

“Indeed you have,” said Serge. “Would you like to repeat any galleries?”

Chuck grinned. “I think I’m good.”

“You said you wanted to see everything,” I said.

“I didn’t know how much everything was.”

Serge guided us back into the gallery and asked, “Have you been to the Louvre yet?”

“Not yet,” said Chuck.

“Best to go on the late night. The crowds will overwhelm on the first visit.”

“When’s that?”

“Wednesday and Friday. The summer is crowded as one would expect,” said Serge.

Serge led us to the first floor restaurant and sat us at a table on whimsical, colorful plastic chairs that didn’t go at all with the baroque interior of gold-painted woodwork and chandeliers. He hurried off to find a member of the staff since the restaurant wouldn’t actually open until 11:45.

“They don’t do anything small here, do they?” asked Chuck, looking at the twenty-foot windows.

“Clearly, you haven’t been to any of the café bathrooms yet.”

“I’m blessed with a big bladder.”

“Showoff.”

“Always.” He took my hand and kissed it. “When was the last time you were here?”

I kissed his hand in return. “In the fall after Honduras.”

“I thought you went to Venice.”

“We did.”

He shook his head. “Being a Bled is a whole other world.”

“I’m not a Bled,” I said.

“We’re in a restaurant that doesn’t open for another three hours and getting the grand tour. You’re a Bled. Face it, baby.”

“It’s more like two hours,” I said as the manager hustled over and asked what we’d like. He looked nervous, for some reason, and Chuck gave me a look. We ordered café crème and éclairs. I was afraid Aaron would turn up his nose at museum pastry, but he was good, eating in silence. Serge came back and sipped an espresso. He wanted something, but he was having a hard time asking for it.

“I can’t stand it, Serge,” I said after listening to him beat around the bush for five minutes. The museum had opened and he glanced repeatedly at the growing din through the doors to the main gallery.

“You know the director does not like to ask anything of your family,” he said after a protracted hesitation.

Chuck cocked an eyebrow at me and I gave him a gentle kick. The big snot.

“I know, Serge. What is it?”

“You must understand this is my idea alone and I am responsible for this query.”

“Now I’m intrigued.”

He finished his espresso and it gave him caffeinated courage. “I have been recently made aware that there are certain pieces in The Bled Collection that the museum and, indeed, the world have never seen.”

I dabbed a bit of chocolate icing off my lip instead of licking it off. The Girls would be so pleased. “What pieces?” I feared he would say something about the Holocaust pieces that Stella had smuggled out. There were several works the museum would love to get ahold of, but there was nothing I could do for Serge when it came to them. The Girls didn’t consider the pieces to be theirs. They were only caretakers until their owners claimed them.

He cleared his throat. “Early sketches of several master works, possibly some Degas, Monet and others.”

“Huh?”

A breath whooshed out of Serge. “You aren’t aware of these pieces?”

“Well…no. They have sketches, but I can’t remember any by Degas or the Impressionists.” I thought Serge would cry, he looked so disappointed.

“My information must be incorrect. I was hoping to mount an exhibit focusing on the artist’s planning stages.”

“Where did you hear that the Bleds had them?” I asked.

Serge pulled a slim sheath of paper out of his breast pocket. “These are copies of letters between Paul Durand-Ruel to Alice, Monet’s second wife. He wanted to buy some early sketches and Alice says that Elias Bled had bought them when Monet wasn’t selling.”

“Oh, that’s a different story,” I said. “Elias’s collection is separate from the Bled Collection. I don’t know what it includes.”

“Then there’s hope.” Serge gave me the sheath and I opened them to squint at the letters written in French. I could read it to some extent, but I wasn’t seeing any titles.

“Which ones did Elias buy?” I asked.

“That is unclear. I believe they were from the period of Monet’s first marriage to Camille.”

I glanced at the visitors outside the door of the restaurant, scanning the menu before eyeing us, sipping our coffee well before opening. The book shop would be open for business but not too crowded. I could hopefully get a good look at Corrine Sweet. “Serge, I don’t know exactly what’s in the Elias Collection, but I can find out.”

“Thank you, Miss Watts. Such an exhibition would be a triumph for the museum.”

I smiled. “Especially if the sketches have never been seen before.”

“Indeed.”

“And a big deal for you,” said Chuck, giving Serge a critical look, but Serge was unfazed.

“This would help my career. Yes.”

The men eyed each other. If I didn’t know better, I’d say Chuck was jealous, but I couldn’t imagine why. Serge and I had zero chemistry. Any fool could see that. He was gay, for crying out loud. Maybe I should’ve mentioned that to Chuck, although it hardly seemed relevant to a museum tour.

“So…maybe we could have dinner together while we’re here and discuss the Elias Collection,” I said.

Chuck scowled down into his cup and Serge’s smooth brow furrowed. Then he darted a look at me and I shrugged one shoulder. A little light went on in Serge’s eyes, and being ever so helpful, he said, “Oh, yes. I would enjoy that immensely and so would Roman.”

“Roman?” asked Chuck.

“My partner. He discovered a new bistro in the seventeenth that I would like to try.”

Chuck straightened up and was all smiles. “That’d be great. What night would be good for you two?”

“Perhaps Saturday or—”

I cut Serge off. “Okay. You guys work it out and I’m going to hit the ladies’ room.”

They barely glanced at me as they bonded over the bistro that cooked their chicken by hanging them from strings in front of a fireplace. They thought it was cool. It sounded like a mess to me.

I excused myself and went out into the crowded corridor. It’d been forever since I’d been to Paris in the high season. I’d forgotten how many tourists there could be. I wove between strollers, walkers and people who were too busy looking at the view to watch where

they were going and headed for the stairs. That was the one place nobody else was. The elevators had a line though.

The book shop sat in a corner on the ground floor and had about six times the people in it than I expected. What the heck, people? You buy stuff first before actually looking at the art? Seriously? I squeezed through the door between two Austrians with their babies in backpacks and worked my way around the tables stacked with art books and biographies. Two employees assisted customers, recommending different titles. Either could’ve been Corrine Sweet, except that they both had light French accents. Where was she? I didn’t have much time. Chuck was going to think I was up to something and I couldn’t afford that. I leafed through a history of Impressionism, casually glancing around and checking my phone for the time. Going on twelve minutes. Not good. Come on, Corrine. We need you. Five Asian ladies, laden with enormous purses, came in, each with a look of needing assistance and taking up half the space.

A third male employee came out of a nondescript door with a stack of Pissarro bios and put them on an already over-burdened table. I squeezed between the Austrians toward the door. Corinne could be back there. I wasn’t quite sure if I had the nerve to open the door. Explaining that wouldn’t be easy without claiming to be an idiot and I hated to do that as a general rule. I looked like an idiot often enough without doing it on purpose.

Still, the shop was getting more crowded and no one else came out to help. I had to give up or come back with Chuck, which wasn’t ideal. I had every faith that the detective in him would pick up my intentions. Obviously, I didn’t need any art books. The Girls had cornered the market and I had a bookshelf full of them. He wouldn’t buy it. Never. No way. I had to try the door and plead ignorance.

I reached the door and went for the knob when a voice said, “Mercy?” My hand snapped back so fast that I punched myself in the stomach before I turned around with a fixed look of innocence on my face. Chuck wouldn’t buy it. I was so screwed.

Serge frowned at me between two of the Asian ladies. I glanced around frantically, looking for Chuck. He wasn’t there and I blew out a breath as Serge came over. “I thought you were going to the toilette.”

A Monster's Paradise (Away From Whipplethorn Book Three)

A Monster's Paradise (Away From Whipplethorn Book Three) A Sin and a Shame (A Mercy Watts Short)

A Sin and a Shame (A Mercy Watts Short) Fierce Creatures (Away From Whipplethorn Book Two)

Fierce Creatures (Away From Whipplethorn Book Two) Strangers in Venice

Strangers in Venice Mean Evergreen (Mercy Watts Mysteries Book Twelve)

Mean Evergreen (Mercy Watts Mysteries Book Twelve) Down and Dirty (Mercy Watts Mysteries Book 9)

Down and Dirty (Mercy Watts Mysteries Book 9) Small Time Crime (Mercy Watts Mysteries Book 10)

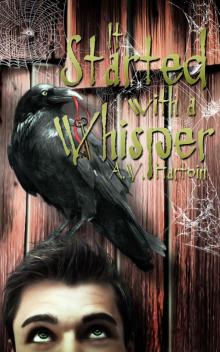

Small Time Crime (Mercy Watts Mysteries Book 10) It Started with a Whisper

It Started with a Whisper My Bad Grandad

My Bad Grandad A.W. Hartoin - Mercy Watts 04 - Drop Dead Red

A.W. Hartoin - Mercy Watts 04 - Drop Dead Red Brain Trust

Brain Trust In the Worst Way (Mercy Watts Mysteries Book 5)

In the Worst Way (Mercy Watts Mysteries Book 5) Diver Down (Mercy Watts Mysteries)

Diver Down (Mercy Watts Mysteries) Nowhere Fast (A Mercy Watts Short)

Nowhere Fast (A Mercy Watts Short) Touch and Go (A Mercy Watts Short)

Touch and Go (A Mercy Watts Short) The Wife of Riley (Mercy Watts Mysteries Book 6)

The Wife of Riley (Mercy Watts Mysteries Book 6) A Good Man Gone (Mercy Watts Mysteries)

A Good Man Gone (Mercy Watts Mysteries) The Wife of Riley

The Wife of Riley A Fairy's Guide to Disaster

A Fairy's Guide to Disaster Coke with a Twist (A Mercy Watts short)

Coke with a Twist (A Mercy Watts short) Dry Spell: A Mercy Watts Short

Dry Spell: A Mercy Watts Short