- Home

- A W Hartoin

A Good Man Gone (Mercy Watts Mysteries) Page 15

A Good Man Gone (Mercy Watts Mysteries) Read online

Page 15

Mom took off Dad’s stained shirt and we got a view of his sunken chest. Mom and I pulled on a fresh pajama top. I’d never seen him wear one before. Dad had pajamas although he never wore them. He usually slept in boxer shorts and he wasn’t shy. He was known to answer the door first thing in the morning without adding to his wardrobe. And by God if he wanted to get the paper like that, he did. As a teenager, I complained that my friends didn’t want to see him in his skivvies. Dad couldn’t see why they’d care. He couldn’t care less what they wore. Half the time, I would’ve sworn that he didn’t see them at all, unless they said something that interested him, which was rare.

Since I was the nurse, I had to do the IV. Dad’s arms looked like he’d been bludgeoned. I hated the idea of poking a needle into those traumatized arms. I might’ve asked Pete to do it, but I’d look like a wuss. So I pictured Dad as an intravenous drug user -- he had the body -- and got started. I blew three veins and got lucky on the fourth stick. Dad was so out of it, he barely complained. I hooked the bag on a coat hanger and hung it on the headboard. Pete measured out a dose of Zofran and injected it into the IV line.

“That should take care of the nausea and vomiting,” Pete said. Then he looked at me. “You can give him another two cc’s in a couple of hours, if you think he needs it. We’ll see how he’s doing then and reevaluate.”

“So you don’t think he’ll need to go to the hospital?” Mom asked.

“I don’t think so, but he’s right on the edge. It depends on how he responds to the Zofran and if we can get him hydrated in a reasonable amount of time.”

“What’s a reasonable amount of time?” said Mom.

“I’d like to see him hold something down within two hours. Apple juice or a cracker will do.”

“I’m certain he’ll be able to do that now that he’s medicated. Why don’t you two go downstairs while I put his pajama bottoms on?”

Pete and I went down to the kitchen. I found a can of Jolt for Pete and made hot chocolate for myself. I needed it, even if it was ninety degrees outside.

“I can’t believe an airline would let him fly in that condition,” Pete said.

“Dad can be very persuasive.”

“I still don’t see how he talked them into it.”

“Let’s just say he knows people,” I said with a smile.

“People in high places?”

“And low places. All layers of the stratosphere really, and they all owe him or want him to owe them.”

“Airlines have regulations about illness and injury. It doesn’t matter who you are or know. Someone wasn’t doing their job.” Pete frowned at me. I didn’t respond immediately and his gaze hardened. People shouldn’t break the rules and certainly not because they admired or feared someone. Debts should never be considered. Rules were rules and for the world to run correctly, they must be obeyed. Pete didn’t live in Dad’s world. I didn’t either, but I visited on a regular basis.

“Well, you know how overworked all those airline people are. They’re more concerned with keeping weapons off planes than viruses, I imagine.” I looked into Pete’s blue eyes and tried to look as innocent as possible. I loved his big eyes with their heavy fringe of lashes, almost feminine in their thickness. His expression changed from suspicious to affectionate and he relaxed. He pushed back and balanced his chair on its hind legs. He looked elegant and easy. I could smell his scent despite the distance between us. I filled my lungs with it. Pete smelled like the color forest green looks.

“Light day?” I asked.

“Yes, we’re nearly empty. Why do you ask?”

“You smell good,” I said and Pete laughed quietly. Mom walked into the kitchen. She had a funny look on her face like she was intruding, which she wasn’t.

“I just thought I’d get some juice and crackers for Dad,” she said as she walked past us into the butler’s pantry. We listened to her search until she came back into the kitchen empty-handed. “I think we’re out of saltines.”

Pete stood up. “I’ll get some.”

“Good. Could you pick up some smoky cheddar, too? Tommy likes it when he’s sick.”

“How do you know?” I asked. “Dad hasn’t been sick in twenty years.”

“Well, he liked it twenty years ago. Stop arguing. You’re as bad as he is and drop those casseroles on your way.” Mom pointed to the dishes that The Girls had brought their famous casseroles over in. Pete picked them up and I told Mom we’d head to The Girls’ house first.

Chapter Fifteen

THE BLED MANSION lorded over the avenue six houses down and across the street, past the invisible line that separated the upper class from the truly rich. Hawthorne Avenue was a gated street so from the outside we were all lumped in together. It takes bucks to be gated, but on my parents’ half of the street those bucks could’ve been earned the hard way. Doctors, lawyers and businesspeople owned those houses. The rest of the street was another story. Those people didn’t work for corporations, they owned them. Their mansions ran in the high seven figures, but it was rare for one to come on the market. The last time was five years ago and caused quite a stir. Highpoint House went for a cool million seven to the heir of the Lange auto empire and a sigh of relief was breathed by the neighborhood. They lived in constant fear that someone would buy in and try to commercialize their world for boutiques or bed-and-breakfasts.

Myrtle and Millicent Bled didn’t worry about such trivial concerns. I doubted they realized that anyone could or would want to change the world in which they’d lived their entire lives. They lived in the house they’d been born in, been raised by nannies in and received their ultra-private tutored education in. As far as I could tell they had no desire for a different kind of life, but they would hardly have spoken to me about it if they had. In many ways, I was like their child. I, too, was born in the Bled mansion, delivered by a private medical staff and surrounded by an unbelievable collection of art, including framed leaves from the Gutenberg bible, a Matisse, a Degas, and a Vermeer sketch. The Girls said I should be born in the presence of greatness and so I was. The Girls had insisted on caring for my mother at the end of her pregnancy. They liked to call it her confinement. Neither of my parents denied The Girls anything, since they loved them and owed them for their entrance into the exclusive world of Hawthorne Avenue. Neither Myrtle nor Millicent said that we owed them. They didn’t operate that way. I think they fell in love with my parents and did as they pleased. The Girls wanted to give them a house, so they did. They wanted to care for my mother and they did that, too. There was no question of Myrtle and Millicent’s intentions — they were good, always good, even if they infringed on our lives a bit.

“I love this street,” said Pete as we crossed Hawthorne Avenue. “I never knew it was here until we met. It’s like another world.”

“It is another world, believe me.”

My phone rang, but it was an unknown number, not Dad having a seizure. I let it go to voicemail. I could check the heavy breathing later.

“It must’ve been strange growing up here with all these rich people and your dad being a cop. No offense, but you know what I mean.”

“I do and it was, but I think they always liked having us here. Dad made them feel safe when the neighborhoods around them were going down the crapper. He used to check out their security for them and install new locks. The rich can be pretty paranoid.”

“Did they pay him?”

“Are you kidding? The rich don’t pay; they expect.”

“That’s nice. All the money in the world and they won’t pay some guy to put locks in for them. They make your dad do it for free.”

“It’s not about the money. It’s about trust. Dad’s a known entity. He’s a cop and lives here.”

“He’s one of them.”

“Sort of. Close as a regular guy can get and still be able to install locks.”

“Does he still change their locks for them?”

“He would if it came up.”

“It’s the next one. The one with the green marble columns.”

“Whoa. I’ve seen it before in some book. I can’t remember which one,” he said as my phone rang again.

He took it out of my hand and said, “Hello.”

“Who is it?” I asked.

“Do you do private parties?” Pete asked with a big grin.

“Shut up!”

“They’ll pay three thousand for two hours.”

“That’ll happen.” I took the phone and switched it off. Dad probably wouldn’t die in the next ten minutes.

We stopped at the front gate and I pushed the buzzer. It made a little buzzing noise that made me think I was about to be electrocuted. A couple minutes later there was another buzz and the eight-foot-high black wrought iron gate swung open. We walked through the gate and I looked up at Pete. He stared up at the house, his eyes jumping around as if they didn’t know where to land. I’d seen plenty of people look at the house that way. It was that kind of house. It wasn’t unusual to see a tripod set up across the street with a camera clicking away or an art student working over a sketchbook. It wasn’t hard to see why; the house was just plain weird. Nicoli Bled, The Girls’ father, built it in 1920 after Prohibition was passed. He took the act as a personal attack since the family fortunes were linked with the consumption of beer. The house was his act of defiance again the whims of public opinion. He wanted it to be noticed and it was.

I stood by Pete, looking up at the mansion with my own feelings of devotion. It was big by Art Deco standards, but whether it truly was Art Deco was difficult to say. The mansion was two exaggerated stories high. In any other building, it would’ve been three. The main structure was rectangular with a flat roof and rounded corners with the exterior covered in pale gray stucco. Four green marble columns decorated the front façade. It was the columns that caught the passerby’s eye. They were huge and spanned the height of the building and bowed out against the house like a child blew them up with a tire pump. Large green ceramic tiles, each with hand-painted palm fronds, edged the top and bottom of the house all the way around. All the many windows were covered in black wrought iron in geometric shapes. None of the windows matched and on either side of the building were glass rooms that The Girls called conservatories. Neither conservatory had walls; only iron columns that held up the flat ceiling. The panes of glass were held in place with elaborate ironwork that suggested Egyptian hieroglyphics, although there were no people done in iron.

It was dusk in the Central West End and a single light above the front door beckoned us to come forward. It wasn’t the welcoming sight I was used to. The conservatories were usually lit to show off their beauty. The Girls liked light. They rarely turned off any switch. In recent years, Dad had gotten them hooked on a computerized lighting system. They liked to fiddle with it and turn the lights to different intensities, have some go on or off at special times of the day. The last I’d heard, Millicent was trying to program the garden walkways to follow a musical program. But that night, it was all dark, even the stained glass windows. I felt weird about going up to the door. The Girls were home, they buzzed us in, but the house was all wrong. I looked around and realized the grass was uncut and there were leaves floating in the four fountains, the water, for once in my life, not gushing.

“It looks abandoned,” said Pete.

“I know. It’s weird. I wonder if the lighting program got fried,” I said.

We walked up the marble steps to the oversized front entrance. The doors themselves were recessed by a foot and encased in more ironwork. I reached through and lifted the iron crow that served as a knocker. I dropped it and it made a heavy plinking noise that would echo through the hallways. A second later, Millicent opened the right door half a foot and peered out at us.

“Hello, dear. How are you this evening?”

“I’m fine, Millicent. This is my friend, Dr. Peter Linderhoff. We wanted to return your dishes.” I waited for her to invite us in. She didn’t.

“Thank you, dear. So kind.” Millicent reached back and I heard a buzz and a click. The iron door slid back into the wall. Millicent took the dishes from Pete, apologized for not being more hospitable, said Myrtle was ill, and bade us goodnight. Before I knew it, the door closed and the iron door slid back into place.

“Okay. I know they’re like family, but that was odd,” said Pete.

“Something’s wrong. They love me. They love men. I figured we’d be here until midnight if we weren’t careful.”

We walked back past the neglected fountains and out the gate. Stern’s, the grocery that existed only to serve Hawthorne Avenue, was six blocks away. I held Pete’s hand and we walked there in silence. Pete bought Dad’s crackers and cheese while I tried to think of a way to get in that house.

Chapter Sixteen

MY PARENTS’ HOUSE was silent when we got back. On the second floor, I could hear Mom and Dixie talking in the master bath. It was their habit. If the worst happens, go hang out in the bathroom. I couldn’t throw stones. My best friend, Ellen, and I spent plenty of hours in there, getting ready to go out and discussing our so-called problems. Mom’s bathroom was a sanctuary with a huge claw-footed tub, dressing table with velvet bench and an archway into the dressing room. Dixie was probably crying in a bubble bath, while Mom listened and applied a moisturizing mud mask.

Pete and I went into the guest bedroom and found Dad sleeping. My mother’s cats had emerged from their hiding place and were sitting at the foot of the bed looking like a couple of Egyptian statues.

“So that’s them. The sofa pee-ers,” Pete said, gesturing to the cats.

“Uh-huh. That’s Swish on the left and the other one’s Swat.” I glared at the cats, but they didn’t acknowledge that we’d entered the room.

“Swish and Swat?”

“They have real names on their pedigrees, but we call them like we see them.”

Pete sat on the edge of the bed and looked at the cats. Neither responded. They both stared at Dad and were expressionless. That might sound odd, but those cats had definite expressions. Maybe it had something to do with being well-bred Siamese. My own cat, Skanky, had no expressions. He barely had a brain.

Pete took Dad’s pulse and blood pressure. When he finished, he pronounced him marginally better. As we looked at Dad, Swat stood up, stretched languidly, and walked up the length of Dad’s body. He stood on Dad’s chest. After a few seconds, he sniffed Dad’s nose, sat down, stuck his leg straight up, and cleaned his butt.

“I need a camera,” I said and ran to the office. When I came back, Swat was biting his butt, and Pete was stifling a laugh.

Pete turned red. “I can’t stand it.” He ran out of the room and I heard him laughing in the hall. I shot pictures from every angle until Mom heard the laughter and came in.

“Don’t take pictures, Mercy. That’s not nice,” she said.

“I want to remember this moment.”

Mom shooed the cats off the bed. Pete got paged and left for the hospital. We woke Dad for the cracker test an hour later. He was groggy, but ate half a saltine.

“Why are you smiling?” he asked with narrowed eyes.

“No reason, honey. Go back to sleep,” Mom said.

Dad ignored Mom. “How’s the case?”

“Fine. Try to get some sleep,” I said.

“I don’t need any more sleep. I didn’t come home to sleep.”

“He is better.”

“He’s not better.” Mom pulled the covers up and Dad shooed her away like she shooed the cats.

“Tell me,” Dad said.

“Okay. I photographed the scene, fixed Dixie’s muffler, walked through the church, and talked to Gavin’s last client.” When I said it like that, it sounded like I’d been sitting on my ass.

“That’s all?”

“I went to th

e morgue, too.”

Dad growled and tried to sit up. “I’ll take over from here.”

“That sounds like an excellent plan. Goodnight, Mercy dear,” said Mom.

“An excellent plan? Dad can’t take over stink.”

“It’ll be fine. He might be well enough tomorrow.”

Swat jumped up on the bed and licked his chops. He had an interesting expression on his pointed face. I could’ve sworn he was thinking, “I just cleaned my ass on you. You’re not going anywhere.”

Mom grabbed me by the arm and steered me out of the room, down the stairs, and into the kitchen.

“Can’t you let anything go?” she asked.

“He’s sick as a dog. He’s not going to the bathroom by himself.”

“I know that. It won’t hurt to let him think he’s going to take over, and then you just keep going.”

“What if I don’t want to keep going?”

“Please. I don’t have the energy for this.” Mom rolled her eyes and rubbed her head. Her hair, which had been damp when she came out of the bathroom, had dried into soft curls around her face. She was pretty, much prettier than a woman her age had a right to be. I thanked God for my fortunate gene pool, mixed blessing though it was.

“What am I expected to do now?” I asked.

“What would you have done if we hadn’t gotten a flight?”

“More interviews, I guess.”

“Then it’s settled. Do that.” Mom handed me my purse and indicated I shouldn’t let the door hit me on the way out.

“You want me to leave?”

“Don’t you have to feed Skanky?”

“He has a self-feeder and Dad might get worse.”

“You’re three blocks away. I think I can handle it.”

“Fine, but I want to give him the next dose of Zofran in a half hour. That way we won’t have to worry about nausea during the night and I’ll be by first thing in the morning.”

Mom nodded her assent. Thirty-three minutes later I was out the door and walking home. The door didn’t hit me.

A Monster's Paradise (Away From Whipplethorn Book Three)

A Monster's Paradise (Away From Whipplethorn Book Three) A Sin and a Shame (A Mercy Watts Short)

A Sin and a Shame (A Mercy Watts Short) Fierce Creatures (Away From Whipplethorn Book Two)

Fierce Creatures (Away From Whipplethorn Book Two) Strangers in Venice

Strangers in Venice Mean Evergreen (Mercy Watts Mysteries Book Twelve)

Mean Evergreen (Mercy Watts Mysteries Book Twelve) Down and Dirty (Mercy Watts Mysteries Book 9)

Down and Dirty (Mercy Watts Mysteries Book 9) Small Time Crime (Mercy Watts Mysteries Book 10)

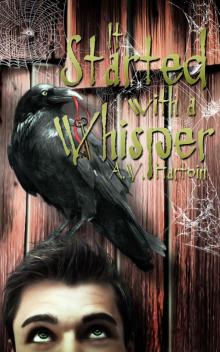

Small Time Crime (Mercy Watts Mysteries Book 10) It Started with a Whisper

It Started with a Whisper My Bad Grandad

My Bad Grandad A.W. Hartoin - Mercy Watts 04 - Drop Dead Red

A.W. Hartoin - Mercy Watts 04 - Drop Dead Red Brain Trust

Brain Trust In the Worst Way (Mercy Watts Mysteries Book 5)

In the Worst Way (Mercy Watts Mysteries Book 5) Diver Down (Mercy Watts Mysteries)

Diver Down (Mercy Watts Mysteries) Nowhere Fast (A Mercy Watts Short)

Nowhere Fast (A Mercy Watts Short) Touch and Go (A Mercy Watts Short)

Touch and Go (A Mercy Watts Short) The Wife of Riley (Mercy Watts Mysteries Book 6)

The Wife of Riley (Mercy Watts Mysteries Book 6) A Good Man Gone (Mercy Watts Mysteries)

A Good Man Gone (Mercy Watts Mysteries) The Wife of Riley

The Wife of Riley A Fairy's Guide to Disaster

A Fairy's Guide to Disaster Coke with a Twist (A Mercy Watts short)

Coke with a Twist (A Mercy Watts short) Dry Spell: A Mercy Watts Short

Dry Spell: A Mercy Watts Short