- Home

- A W Hartoin

A.W. Hartoin - Mercy Watts 04 - Drop Dead Red Page 2

A.W. Hartoin - Mercy Watts 04 - Drop Dead Red Read online

Page 2

“No, I’m not. Ask Dad. He called me a pansy yesterday.”

“Tonight at six.”

“I’ll clean your mustard,” I said, crossing my arms.

“I need a movie-watching partner. It’s no fun without someone to scream with.”

“It’s no fun at all.”

“Do you want to know about the Klinefeld Group?”

“Yes.”

“Then you’ll be here,” said Aunt Miriam.

“I’ll find some other way to get the info.”

“No, you won’t. Don’t make me get out The Exorcist.”

“Please don’t make me do this,” I begged.

Aunt Miriam’s pocket started to ring. It had to be Dad. He never gave up and Aunt Miriam wouldn’t have any problem with caning me to get me to obey.

Aunt Miriam managed to answer it after she tried fifteen different buttons. Cellphones weren’t her thing.

“Hello, Tommy,” she said in a sweeter tone than she ever used for me. Probably because Dad taught self-defense classes to the Sisters of Mercy. That was an idea I wished he’d forget.

Aunt Miriam held up the phone and Dad’s voice exploded out of it. “What are you waiting for? Don’t make me come over there!”

I think there was even a breeze coming out of it.

Aunt Miriam crossed her arms.

“How did he know I wasn’t leaving?” I asked.

“He’s your father. Will you be leaving or shall I make another sandwich for Tommy?”

I stomped out without answering. No good could come of it.

Chapter Two

TRAFFIC BROUGHT ME to a dead stop under a streetlight banner proclaiming in green, white, and red that I had arrived on The Hill. I didn’t need a banner to know where I was. The Hill was unique in the St. Louis landscape. The turn-of-the-century brick buildings were filled with family restaurants and shops that had been in business for decades. The Italian flag’s colors were everywhere, just so you would know exactly what The Hill was all about. Food and family. I loved it. The Hill was cozy and warm on the coldest days and there was a sense of history that could only be matched in the Central West End, where I grew up and still lived. If I ever moved, it would be to The Hill.

I leaned to the left to try and see around a ginormous sport utility vehicle. I got a glimpse of a detour sign and groaned. A cop stepped in front of the sign and waved for the line of vehicles to start moving. I thought I’d make it through, but I got the hand and the cop waved the cross traffic through instead. Macklind Avenue was blocked off and that was where Gioia’s was. Great. I couldn’t see what was going on, but it had been happening for a while. There were cop cars and white tents cordoning off the area.

The cop was replaced by another broad-shouldered man in blue and the first cop headed in my direction. I quickly cranked down the window. “Excuse me!”

He turned, his face drawn and his young eyes accented with heavy bags. It said O’Connor on his name tag. “Yes, ma’am.”

“What’s up with blocking off Macklind? I gotta get to Gioia’s.”

“The detour will get you…” He trailed off as he leaned in to get a better look at me. “Holy crap! You’re Mercy Watts. You really are a dead ringer for Marilyn Monroe. I can’t believe I’m talking to you. I met your father once. He rocks. I mean, he’s a great cop. A great detective, he was, I mean he is. He is a great detective. He was a cop. You know that. Everybody knows that.”

“Breathe,” I said, suppressing a smile. Dad’s fans got so flustered.

“Sorry. I just didn’t think you’d be here. I mean, you have to be somewhere, but not here. You could be here. I can’t believe I’m meeting Tommy Watts’s daughter. You’re the DBD cover girl. Holy crap. Can I have your autograph?” asked O’Connor.

What started out as fun had rapidly turned depressing. I was famous, but not for anything good. I was Tommy Watts’s daughter. DBD’s cover girl. I had Marilyn’s face. None of that was about me, the real me. It was all window dressing. I was famous for belonging to someone else. That stunk. I was supposed to belong to me.

“Sure,” I said with a sigh. “Got paper and a pen?”

He gave me his ticket pad and I signed the cardboard backing. That was a new one.

“So…are you going to tell me what’s going on down there or what?”

“You’re joshing me, aren’t you? You and your dad are probably on the case. Is there a case? They have the guy. Maybe they don’t. Do you know something?” asked O’Connor.

I slapped my forehead. “I don’t even know why I’m sitting here. What happened?”

“Seriously?”

“O’Connor, your partner’s about to wave me through. Tell me or I’ll run you over.”

“Tulio’s down there.”

I blinked.

“The shooting. Mass murder.”

“I…I forgot. I’ve been working a lot,” I said, my stomach growing queasy with the pimento loaf and the thought of all those people.

“What’s the case?” whispered O’Connor. “I won’t tell anyone.”

“I’m a nurse. There’s no case.”

He held his finger to his lips. “Mum’s the word. You are not on this case. Got it.”

Oh dear Lord.

The other cop waved to me and I drove away from O’Connor, who would undoubtedly inform everyone he met that I was working the Tulio mass murder case, which I wasn’t. Like he said, they got the guy. Kent Blankenship had confessed to walking into Tulio, one of The Hill’s best restaurants, and opening fire with a TEC-9. He killed or wounded twenty-six people in the small elegant dining room in the space of 22 seconds before a waitress named Monique Robertson, who bore an uncanny resemblance to the actress Mo’Nique, tackled him. After Blankenship was arrested and charged, his idiot lawyers tried to claim police brutality, only to discover that Monique had brutalized him in every way an unarmed woman possibly could. She kicked him, bit him, punched him, clawed him, and stabbed him with a fork multiple times. Blankenship’s mug shot made him look like the victim, instead of a thirty-year-old busboy that got fired from Tulio’s for incompetence. Monique was lauded as a hero and every news program known to mankind featured her for days. The Tulio case didn’t need me, it had the epically badass Monique.

I had been working a double shift in St. John’s ER the night it happened and I’d done my best to forget about it ever since. The victims didn’t come to our ER, too far away, but it was all over the news. It was a miserable, heartbreaking night made worse by my history. Again, I was famous for all the wrong reasons. People felt compelled to ask my opinion about it because I’d nearly been murdered and was obviously an expert on murderers. Surviving didn’t make me an expert on anything, except for crappy hospital food, but nobody believed that. Nobody except Dad and my cousin by marriage, Chuck. They got that you can solve a crime, see the motive, and not truly see the person behind it. Murderers were all unique and they kept escaping their pigeonholes, no matter how often we stuffed them in there.

Why in the world did Dad decide to have lunch at Gioia’s on that day of all days? Blankenship had done his deed three days before. I loved The Hill, but it was the place to avoid on that afternoon. If I hadn’t been so good at blocking out Tulio, I would’ve insisted on having lunch somewhere else. I didn’t care if Gioia’s had the best salami in the world, thinking about Tulio was too high a price to pay.

I followed the detour signs in a roundabout way through the backstreets of The Hill. I wasn’t sure why twenty turns were needed to get me to the other side of Macklind, but the cops seemed to think it was necessary. My truck barely fit into a parking space down the street from Gioia’s. The street wasn’t that crowded on a Saturday night. Gawkers and news people had taken up all the spaces, and I hoped they were spending money at the places that didn’t have the misfortune to hire homicidal busboys.

Gioia’s was packed, but it always was. I squeezed in the door and spotted Dad at one of the few rickety metal tables. Th

e line wrapped around him, crowding his tall, spare form, but he ignored them. Dad was hunched over a tablet, typing in notes with amazing speed.

I pushed past a couple guys discussing the merits of Italian-style beef and headed for Dad. Before I made it, I was cut off by Joe Funaro, a local baker.

“Hey, Mercy. Thought I might be seeing you, since the old man is here.”

“It’s under duress, I assure you.”

“Yeah, I get it. Your dad is something. So what do you make of that whole deal down at Tulio? That’s some shit, ain’t it? I can’t get nothing out of Tommy,” said Joe.

“To tell you the truth, I’d forgotten all about it,” I said, trying to maneuver past him.

“You forgot? It’s all over Headline News.” He leaned to the side and looked out the plate glass window. “There’s a rumor that Robin Meade might come out to cover the trial.” He gave me a rakish look. “What do you think? Do I have a shot?”

I rolled my eyes. “Not even a little bit.”

“Hey! Give a guy some hope.”

“First of all, Robin Meade doesn’t cover trials. She sits in the studio. Second, she’s married.”

“She’s a Hollywood type. They don’t mate for life,” said Joe.

“Or for a decade, usually,” I said.

“Exactly my point. Do you think I should get my chest waxed?”

“Please don’t,” I said, shuddering. Joe’s hairless chest didn’t bear thinking about.

“But girls like it,” he said

“Not all girls. I still have a huge crush on Magnum P.I.” I slipped away, leaving Joe to ponder Tom Selleck.

I sat in a chair next to Dad and said, “Why here? Seriously, why?”

Dad glanced up, but not at me. Our table was being eyed by customers desperate for a table. There was a conspicuous bulge under his right arm. Being armed helps when you’re not vacating quickly. Tables were at a premium and we were going to be there for a while. Dad had two unwrapped sandwiches in front of him, some bags of my beloved Billy Goat chips, and a couple of iced teas. Dad’s would have a pound of sugar in his. Mom was from the South, but it was Dad who loved the sweet tea.

“It’s the right place. You needed to be down here today,” he said, still eyeing the customers until they backed off.

“Why would I need to be here today? Traffic is a nightmare,” I said.

I got you a Sydwich,” he said with the lazy smile he was said to use on suspects quite effectively. It lured them in. I refused to be lured.

I crossed my arms. “Dad, I don’t like Sydwiches. That’s you.”

“Damn. Honest mistake.” He rubbed his hands together. “I guess I’ll have to eat them both.”

Honest mistake, my foot.

“What’s Mom going to say?” I asked.

He grinned, stretching his freckles and popping out his ever-so-charming dimples. “Nothing. My ulcer has resolved.”

“Really?”

“Really. What sandwich do you want?”

“Nothing. Aunt Miriam fed me pimento loaf and Tang,” I said.

He sneered. “You need real food.”

“Just a salami,” I said.

Dad raised a long arm. “Shrimpy, a salami on garlic cheese.”

“On it!” hollered Shrimpy, one of the expert sandwich makers, from the back.

The rest of the patrons stared at us, mouths open. The service at Gioia’s was iffy. They were busy, having the best freaking salami in the world will do that, so they didn’t have time for the niceties.

Fifteen seconds later, Shrimp yelled, “Incoming!” He launched my sandwich in the shape of a white papered torpedo across the dining area, Dad’s long arm shot up and snatched it out of the air. “Thanks!”

“You want some tortellini salad with that, Tommy?”

I held up my hand. “No, no. I’m good.” Nobody needed a container of tortellini flying around.

“It’s a pass, Shrimpy!” yelled Dad.

“Sure thing!”

I unwrapped perfection and breathed deep the smell of a century-old recipe. The garlic cheese bread didn’t hurt either. But before I took a bite, I asked, “So Dad, why are we here?”

“Ameche. What’d you think?”

“Ameche?” I took a bite. Oh my god. Why’d I eat that pimento loaf? I’d wasted valuable stomach space.

“He’s your people. You gotta be on this.”

“Ameche isn’t my anything. What are you talking about?”

“He’s your people. You got to take care of your people.”

I sipped my tea, unsweet and therefore palatable. “He helped me with a case one time. That hardly makes us attached at the hip.”

Dad inhaled a Sydwich and gulped his tea to cool down the spicy giardiniera. “Where’s your loyalty? I raised you better than that.”

Dad didn’t do much raising to be honest. He was an up-and-coming homicide detective when I was young and worked as much as possible. Sometimes more. Most of my raising was left to Mom and my godmothers, Myrtle and Millicent Bled. Dad filled the role of pain in the butt. He still did, eyeing me while he unwrapped his second Sydwich, having lost all the charm he used on suspects.

I chewed slowly, just to bother him, and then said, “Fine. What’s wrong with Ameche?”

“Haven’t you been watching the news at all?”

“No. I’ve been avoiding it like herpes.”

Dad started on his second Sydwich and then pondered me. “The incident at Tulio really bothered you?”

“Of course. I’m not a fangirl for murder. And I wouldn’t call it an incident. It was horrific.”

He reached over and pulled me close. His forehead touched mine and a lock of his red hair brushed my forehead. It was tender and comforting, not like Dad at all.

“Just tell me. I can’t take the suspense,” I said.

“I’m sorry you have to be involved.”

I jerked back. “I don’t.”

“You do, I’m afraid. You met Ameche’s sister, Donatella?”

“No. Why?”

“Her husband and his entire immediate family were killed at Tulio.” Dad’s voice was soft and steady, no ups or downs. They were just words that couldn’t hurt me, but somehow still did.

My sandwich stopped halfway to my mouth and Dad pushed it back down to the paper. “Mercy?”

“There were kids in there,” I said.

“Two nephews and a niece.”

“Oh my god. Have you talked to Ameche?”

“He called me this morning. There’s an issue with Donatella and he needs our help, your help specifically.”

“My help? What for?” I asked, my throat dry and scratchy.

Dad pushed my sandwich closer. “I’ll tell you. Eat up.”

“I’m not hungry anymore.”

He nodded and told me about Donatella Ameche Berry and Tulio. Donatella was Ameche’s older sister. She was married and lived in New Orleans. Friday, the night of the murders, was her in-laws 40th wedding anniversary. The family was celebrating at Tulio. Donatella’s husband, Rob, flew in on Thursday to spend some extra time with his family and Donatella was supposed to fly in after the kids got out of school on Friday. Their flight was at five. Donatella pulled the kids out early and managed to get on an earlier flight so they wouldn’t have to go straight to Tulio from the airport. That change in plans saved her kids’ lives. They became violently ill on the plane and an ambulance met them on the tarmac. They made it to the hospital in time and were diagnosed with a form of bacterial meningitis that would’ve killed them in flight, had Donatella stuck to the original schedule. As it was, she and the kids were at the hospital when the shooting at Tulio took place. Once the kids were out of immediate danger, Rob went to the restaurant to tell the family what had happened. He was there in time for dessert and for Kent Blankenship to open fire.

Dad wrapped my hands around my iced tea and insisted I take a drink. It was hard to get a sip down, my throat was so dry.

�

��They’re all dead?” I choked out.

“Yes. All of the Berrys that were there. They had the misfortune to be seated in the center of the restaurant because of the size of the table. Line of fire.”

“That might be the worst thing I’ve ever heard.”

“I’m not done,” said Dad.

I looked up into his blue eyes. They were so much like Aunt Miriam’s, but without the critical appraisal for once. “Donatella’s kids?”

“Still alive. Still in the ICU.”

“So…”

“There are surviving Berrys, the ones not invited to the anniversary dinner, and they think Donatella hired Blankenship to kill her husband and his family.”

“Are you freaking kidding me?” My cheeks flushed and the top popped off my cup.

“Nope. That crew is on fire and they blame Donatella for the massacre.”

“I thought Blankenship confessed.”

“He did, but they’re pushing for an investigation into Donatella.” Dad sucked the last ounce of sweet tea out of his giant cup.

“Her kids almost died. Are they crazy?”

“Ameche says they’re dirtbags and the dirtbags think the meningitis was pretty convenient for Donatella, since it saved her life and the kids’ lives.”

“What do they think, that she gave them meningitis?” I asked.

“That’s exactly what they think and they’re pushing hard.”

“Who has the case?”

Please don’t say Chuck.

“Sidney Wick. Good guy and he’s taking it seriously.”

“Ameche must be totally losing it.”

“That’s putting it mildly.”

I wrapped up my sandwich for later. One does not throw away a Gioia’s salami, even when one thinks they might throw up. “I’m so afraid to ask, but what do you want me to do? I assume Blankenship didn’t implicate Donatella, so this isn’t going anywhere.”

Dad shook his head. “You’ve been around, Mercy. That isn’t close to the end of it. People have been sent to death row on nothing more than circumstantial evidence.”

“And I’m supposed to…”

“You’re a nurse. I want you to nip this in the bud. Talk to the doctor and find out if it’s remotely possible that Donatella could’ve orchestrated this illness thing. Off the top of your head, what do you think?”

A Monster's Paradise (Away From Whipplethorn Book Three)

A Monster's Paradise (Away From Whipplethorn Book Three) A Sin and a Shame (A Mercy Watts Short)

A Sin and a Shame (A Mercy Watts Short) Fierce Creatures (Away From Whipplethorn Book Two)

Fierce Creatures (Away From Whipplethorn Book Two) Strangers in Venice

Strangers in Venice Mean Evergreen (Mercy Watts Mysteries Book Twelve)

Mean Evergreen (Mercy Watts Mysteries Book Twelve) Down and Dirty (Mercy Watts Mysteries Book 9)

Down and Dirty (Mercy Watts Mysteries Book 9) Small Time Crime (Mercy Watts Mysteries Book 10)

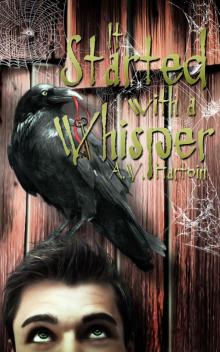

Small Time Crime (Mercy Watts Mysteries Book 10) It Started with a Whisper

It Started with a Whisper My Bad Grandad

My Bad Grandad A.W. Hartoin - Mercy Watts 04 - Drop Dead Red

A.W. Hartoin - Mercy Watts 04 - Drop Dead Red Brain Trust

Brain Trust In the Worst Way (Mercy Watts Mysteries Book 5)

In the Worst Way (Mercy Watts Mysteries Book 5) Diver Down (Mercy Watts Mysteries)

Diver Down (Mercy Watts Mysteries) Nowhere Fast (A Mercy Watts Short)

Nowhere Fast (A Mercy Watts Short) Touch and Go (A Mercy Watts Short)

Touch and Go (A Mercy Watts Short) The Wife of Riley (Mercy Watts Mysteries Book 6)

The Wife of Riley (Mercy Watts Mysteries Book 6) A Good Man Gone (Mercy Watts Mysteries)

A Good Man Gone (Mercy Watts Mysteries) The Wife of Riley

The Wife of Riley A Fairy's Guide to Disaster

A Fairy's Guide to Disaster Coke with a Twist (A Mercy Watts short)

Coke with a Twist (A Mercy Watts short) Dry Spell: A Mercy Watts Short

Dry Spell: A Mercy Watts Short