- Home

- A W Hartoin

A Good Man Gone (Mercy Watts Mysteries) Page 26

A Good Man Gone (Mercy Watts Mysteries) Read online

Page 26

“Excuse me,” said Lee, his voice barely audible. I felt like he was looking through my head when he said it.

“I’m so sorry, Lee,” I said.

“Excuse us, Detective Watts. We have to go in,” said the reverend.

They brushed past me and I stood for a moment face-to-face with Lee’s brother, Darrell. He glared at me and started to speak, but blue eye shadow girl came out of Remembrance One and did another about-face.

Not so fast, sister.

I chased her down. I wasn’t going back into Remembrance Three no matter what.

“We need that price list now,” I said.

She muttered some excuses, but I held her arm and she relented. We walked into the hall, down the ramp into the showroom. Aunt Miriam started quizzing her on each casket, price, paint quality, availability. She talked and talked. The girl listened and would’ve agreed to anything just to escape Aunt Miriam. I knew the feeling. Blue eye shadow girl pulled out some paperwork from behind the Eternity Gold and asked Aunt Miriam to sign the order. Lee Holtmeyer popped into my head, him signing the guest book. Morty said Lee’s name was in the Wilson Novelties book. He signed it. He was there. Lee was in Lincoln and he lied about it.

“Oh my God. Aunt Miriam. Oh my God.”

“Mercy Watts, have some decorum and respect. I’m trying to negotiate here.”

“But Aunt Miriam…”

“Please be quiet. It’s nothing that can’t wait.”

“No. I’m telling you it cannot wait.”

“Mercy, please.”

“Fine.” I pulled out my phone.

“Mercy, how many times do I have to tell you?” Aunt Miriam made a chopping motion towards the door. I glared at her and walked out. I wouldn’t have thought it possible, but the hall was even more packed. I pushed through to Remembrance Two and gave up. I dialed Chuck’s desk. It killed me to do it, but Dad was still out. Chuck, as sleazy as he was, was a great cop.

Somebody answered the phone, but I couldn’t make out what he said. “Chuck. Chuck. Is that you? I’m looking for Detective Watts.”

I couldn’t make out a word. My phone was useless in there. No one would be able to hear me and I’d never make it to the front door. The exit in Remembrance Two was worse than the hall. I rotated and spotted an unmarked door. At the very least it led out of the crush, so I took it. It was a storage room packed with extra chairs, baseball equipment, broken podiums and, ick, more caskets. They should keep that door locked. Lucky for me it also had an exit. The red sign glowed behind a stack of chairs. I pulled on them and they fell over on a red casket creating a huge gash in the lid.

Great, just great. Wait, it wasn’t my fault. They should’ve kept that door locked plus it’s red. Who gets buried in red? Prostitutes and adulterers maybe.

I pushed on the metal bar on the exit door and sunlight blinded me. I hadn’t realized how dim it was inside. I leaned my hip on the door, thrusting it open further, and propped it open with a dented brass ashtray.

I hit redial on my phone.

“Detective Clancy.”

“Detective Clancy? Isn’t this Watts’s desk?”

“Yeah it is. Can I help you?”

“No. I need Watts right now,” I said. “It’s an emergency.”

“Tell me who you are and what the emergency is. Then I’ll get him.”

“Mercy Watts. It’s about the Sample Flouder case. Get him now!”

“So which case do you want to talk to him about, Sample or Flouder?”

“Oh my god! They’re the same case.”

“Okay. Okay. Don’t get your panties in a twist.”

The door screeched open and I slipped behind another stack of chairs. The door closed and I heard the unmistakable sound of a gun cocking. I shifted sideways and peeked around the chairs. Darrell. Of course. Big brother come to fix the problem once again.

Darrell’s eyes slid around the storage room and settled on the exit door to my left. “God damn it.”

The baseball bats were across the room. I’d never get to them. Darrell came closer. If he went all the way to the door, he’d see me. I held my breath.

I’m not here. I got away. Go back.

He kept walking; slow, deliberate steps. He was at the door.

“Mercy!” Chuck’s voice came out of my phone.

Darrell’s head snapped to the left. Our eyes met. I grabbed the chairs and toppled them over on him. He yelled as he went down and I heard the metallic clunk of the gun hitting the concrete floor. The chairs settled. They covered Darrell completely, except for his gun hand which was empty and still. I put my hand to my ear and realized my phone wasn’t in it anymore. Like Darrell’s gun it had disappeared in the avalanche of chairs. It also blocked the way to the door into Remembrance Two. I’d have to climb over caskets to get to it.

“Ah crap.”

That was the last thing I said. White starbursts filled my vision and my hands were on either side of my head trying to press out the pain. I was on the floor, my cheek against the cold concrete. I think I was rolling back and forth from the pain, an involuntary movement I’d seen patients make after a severe injury.

Someone touched me. He didn’t speak or at least I didn’t hear anything. He grabbed my arm and pulled it away from my head and started dragging me. The starbursts got brighter and became streaked with red. Through the pain, I knew I was in big trouble. What did Dad say? Never let yourself be taken to the second location. I was going to the second location. I slid over a hump and something snagged my dress. He pulled my arm so hard, I thought it would come out of its socket. Something went through my dress and cut into me. A hot, burning pain went down my back slicing skin from muscle. It was one more pain in a nightmare and worse, I was now outside. Outside. Away from people. The second location.

My arm dropped and I thought he left. My hand went back to my head and then he kicked me, not hard, not the first time. But there wasn’t just one kick, but a half dozen in my ribs and the small of my back. The pain rivaled the pain in my head, but I couldn’t do anything to protect myself. I couldn’t move my hands from my head -- that pain was paramount.

One more kick, a big one, sent me off the edge of something. The fall was short, but it felt like forever. Long enough for me to think, “At least he’s not kicking me anymore.” Then I hit the ground. Apparently, the body can only take so much pain because it didn’t hurt and it should’ve. I could feel sharp rocks under my face and chest. I’d landed sunny-side down. My hands were still at my head, my elbows digging into the ground. My stomach heaved. It wasn’t forceful or even uncomfortable. Warm liquid spilled over my lips and pooled under my cheek, but nothing happened. No more pulling or kicking. The pain didn’t subside or increase, and I began to cope with it. I felt my face and realized that my eyes were closed so I opened them. The pain powered through my head like Aaron through a crab cake. My vision went in and out with starbursts and red streaks going through, but I could see. I was outside on a gravel border about three feet from the funeral home lawn. Beyond the lawn was a stand of trees. I was alone. When I realized I could hear I listened for footsteps and there weren’t any. He was gone and I had a chance.

I rolled back over on my back and looked at the sky, pale blue with fluffy clouds floating past at a good clip. I took a deep breath and forced myself onto my left side. The building was in reach of my fingertips. I cocked my head back. The edge of the parking lot was twenty feet away. The other way was a small porch, the one I’d been kicked off. I couldn’t go that way. He’d come back and that’s the way he’d come. I could crawl out onto the lawn and hope a mourner would spot me when they got in their car. Of course, the guy wouldn’t have a hard time spotting me either, but he’d have to drag me back in a visible area. I could make for the parking lot. I’d be blocked by the cars, but easier to hear. Then again, if he came back, he could drag me into a car and that’d be the end of me.

It came down to what I was capable of, which wasn’t much. The p

ain in my head was getting worse and every breath was fire. Damn it. I had to get moving. I didn’t know how long he’d been gone, but it was too long. I looked up over my hand and saw a water spigot. The piping went up the side of the building and looked sturdy. Maybe if I could drag myself upright I could inch along, using the wall as a brace. It had to be faster than crawling, as long as my head could take it.

I belly crawled to the pipe and grasped the spigot. My hands shook so that I could hardly get them on it. I inched my way up the wall, maneuvered myself until I was in a seated chair position. It wasn’t too bad. My head felt like the Fourth of July, but I was moving. I let go of the pipe and flattened my hands against the wall, spread eagle. I wiggled and slid toward the parking lot. I was feeling pretty good about it, all things considered. I was snail slow, but I could hear the sounds of the road. If I had to, I knew I could scoot around to the front.

Then I bumped into something cold and metallic, a drainpipe. I rolled on the wall and grabbed it with both hands and nearly fell to my knees. A couple of deep breaths and I was ready to move over it.

“Where do you think you’re going?”

I opened my eyes. My nose touched the chipped gray paint of the drainpipe and my breath grew more ragged. She was back. Not him. She. I pulled myself closer to the pipe and put my cheekbone against it and I looked at her. Lee’s mother stood so close I could count the large pores on her cheeks and the clumps of mascara on her lashes. I couldn’t think of a thing to say. All my powers of sarcasm left me and all I had was hot breath and fear.

“You lied to us.” Mrs. Holtmeyer moved in closer and I smelled her breath, coffee and Kahlua.

“Huh?”

“You said you weren’t a cop.”

“I’m not.”

“Detective Watts, the reverend called you, Detective Watts. You lied.”

“I lied to her, so she wouldn’t tell the cops about me.”

“You lied.” She looked at me like lying was the worst thing in the world; worse than, say, murder.

Must stall. I’ll be missed eventually.

“Lee lied,” I said through clenched teeth.

Her head jerked back a couple inches. “Lee does not lie.”

“He lied to Rebecca.”

“He loved her. He never lied to her.”

“He sure as hell never told her he was fucking stalking her.”

“He never hurt her,”

“You’re a fucking idiot.” I knew it was a mistake the second it came out of my mouth. Mrs. Holtmeyer lunged at me, her fingernails going for my face. I swung my cast around and connected with her cheekbone. Her fingers grazed my cheek, but she stumbled and fell at my feet. The movement was too much. I lost my grip on the pipe.

Before I hit the rocks, she was on me, grabbing my hair. “You interfering bitch.” She twisted my head with my hair and pushed my head into the rocks. I like to think I screamed, but I doubt I did. I didn’t have enough air.

“You’ll leave my boys alone now, won’t you,” she said in a low, controlled voice.

I flailed my good arm behind my head and grabbed her wrist. I dug my fingernails into her veins and she screamed. She let go of my hair and grabbed my good wrist. She twisted it behind my back. I heard a pop and a tremendous weight fell on me. My face was driven into the gravel. I forced my head from side to side, trying to make a hollow for air when the weight lifted. I pushed myself over on my side with my cast. Just before I passed out, I saw Aaron looking down at me holding Aunt Miriam’s cane in his hand like a mace.

Chapter Twenty-Nine

I WOKE TO a warm hand stroking my forehead and the smell of good cologne in my nose.

“Dad?”

“No, Chuck.”

I opened my eyes and saw Chuck bent over me. His white dress shirt had the top two buttons undone, revealing his collarbone and a tangle of chest hair. His shield was at his waist and his face had an expression I’d never seen on it before. Maybe distraught. I tried to move my head, but I was in a neck brace and strapped to a backboard.

“We have to stop meeting like this,” he said.

“Stop touching me.”

“Not a chance and you called me. Remember?”

“Go away.” I tried to yell it, but my lungs and jaw wouldn’t let me. If I could’ve grabbed his hand, I might’ve bit him.

“Stay still,” said Chuck. “And stop trying to bite me.”

Someone else knelt beside me and picked up my wrist. I screamed and passed out again. When I woke up, Chuck said, “I guess her lungs are fine.”

Several people laughed and I really wanted to bite him. Cops and EMTs were swarming all over the place. Out of the corner of my eye, I saw another person lying facedown a few feet from me. Chuck saw me looking and said, “That’s Holtmeyer. She’s still alive, unfortunately.”

“They’re all crazy,” I whispered.

“Not crazy enough and we have the death penalty.”

I started to cry, one of those big ugly cries, and I couldn’t even cover my face with my hands.

“I didn’t know you wear thongs,” Chuck said.

“What?” I said.

“Thongs. You wear thongs. I didn’t know you were a thong kind of girl.”

“How do you know I wear thongs?” Just then a breeze hit my stomach and thighs. The tears dried in my eyes and I was back to biting. “Oh my God. Pull my dress down, you sleazebag.”

Chuck tugged on my hem. “I like this dress.”

“I’m glad it’s ruined then.”

Chuck laughed and left me to the EMTs. I watched him walk to the ambulance a few feet away. Aunt Miriam sat on a gurney looking at me with an oxygen mask on her face. Chuck and the ambulance dwarfed her. She looked old and fragile. I wasn’t accustomed to seeing her that way, an old woman.

I closed my eyes and watched the spots dance across my vision. The pain was better, but the IV in my arm could’ve had something to do with that. The EMT told me they were going to transfer me to a gurney for transport to St. John’s. Chuck came back and touched my leg. I thought about kicking him, but found I didn’t care all that much who touched my leg.

They lifted on three and there wasn’t enough drugs on board to control the pain. I screamed until I panted from the effort then a hand touched my forehead. A kiss brushed my cheek and I smelled lavender. Aunt Miriam. The oxygen mask was off and her eyes were inches from mine. She whispered in my ear. I wish I could remember what she said. Mostly I remember her eyes. The blueness of them and how much they looked like Dad’s.

The next twelve hours alternated between hazy suggestions of events and long periods of nothing. I remember the blinding lights of the ER and the pain they caused. I remember my arm being popped back into its socket. I think Chuck and Nazir tried to ask me questions. I might’ve told them to shove it or something like. Pete flitted in and out like a hummingbird. I woke up once as he slept with his head on the edge of my bed, snoring and clutching my chart to his chest. I tried to touch his head, but fell asleep before I managed it.

I didn’t wake up again until the next day. My IV pump alarm was going ape shit and there were two nurse’s aides hitting buttons like a couple of woodpeckers.

“Get the key,” I said.

They both turned and stared at me.

“I’m a nurse.”

“Do you know how to turn this thing off?” It said Peggy on her tag. She didn’t look like a Peggy to me. I wondered if she had the wrong tag.

“You need the key,” I said.

Peg and her partner in stupidity asked each other if they had the key. It was a good thing I wasn’t coding because that would’ve been all she wrote. The more I listened to Peg and Glenda the more likely it seemed that they might not have on the right tags. They might, in fact, be janitors.

“Call the desk,” I said.

I was on a morphine drip, but the noise was increasing my migraine by the second. Peg tried to call the desk on my intercom, but they couldn’t hear her over the al

arm and they both went in search of the key. My mother crossed their path, walking in with a tall pink cake box and coffee.

“Unplug it,” I yelled.

Mom yanked the plug out of the wall, but the alarm kept going. Mom looked at me and I said, “Push it over here.” My formerly good arm was in a sling, but my casted arm was free. I had enough finger mobility to unclip my medication drip from the pump and told Mom to unhook the IV bag. Mom pushed the squealing pump into the hall and closed the door. She took a deep breath and turned around.

“Feeling better, I see,” she said.

“I’m okay.” I stuck out my lower lip. I wanted sympathy, not a positive assessment.

Mom placed the cake box on my rolling table, lowered it to the height of the chair next to my bed and got a fork out of her purse.

“Hey, I said I’m okay.”

“I don’t know if okay is good enough for this cake. This is an extreme dessert.”

“I think I’ll risk it.”

Mom kicked off her shoes, a big no-no in public, and cuddled into my bed beside me. She folded down the sides of the cake box and I got all misty. German chocolate. My favorite made by Myrtle and Millicent. I could tell by the huge dark chocolate curls. They made the best curls.

“Don’t cry,” said Mom, dabbing at my eyes with a tissue.

“It’s my cake and I’ll cry if I want to.”

Then Mom cried a little, although she called it allergies. She has no allergies, the big softy. To distract her I asked if Ellen had come by. Mom said she had, but I was still out of it and Sophie peed on the floor, so she had to go. Mom didn’t approve of Sophie. She said the tiny girl was a hellion. I guess she would know, considering that she’d raised me.

A Monster's Paradise (Away From Whipplethorn Book Three)

A Monster's Paradise (Away From Whipplethorn Book Three) A Sin and a Shame (A Mercy Watts Short)

A Sin and a Shame (A Mercy Watts Short) Fierce Creatures (Away From Whipplethorn Book Two)

Fierce Creatures (Away From Whipplethorn Book Two) Strangers in Venice

Strangers in Venice Mean Evergreen (Mercy Watts Mysteries Book Twelve)

Mean Evergreen (Mercy Watts Mysteries Book Twelve) Down and Dirty (Mercy Watts Mysteries Book 9)

Down and Dirty (Mercy Watts Mysteries Book 9) Small Time Crime (Mercy Watts Mysteries Book 10)

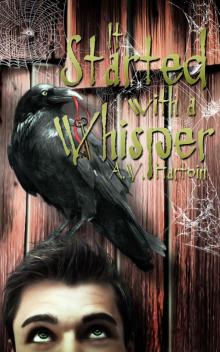

Small Time Crime (Mercy Watts Mysteries Book 10) It Started with a Whisper

It Started with a Whisper My Bad Grandad

My Bad Grandad A.W. Hartoin - Mercy Watts 04 - Drop Dead Red

A.W. Hartoin - Mercy Watts 04 - Drop Dead Red Brain Trust

Brain Trust In the Worst Way (Mercy Watts Mysteries Book 5)

In the Worst Way (Mercy Watts Mysteries Book 5) Diver Down (Mercy Watts Mysteries)

Diver Down (Mercy Watts Mysteries) Nowhere Fast (A Mercy Watts Short)

Nowhere Fast (A Mercy Watts Short) Touch and Go (A Mercy Watts Short)

Touch and Go (A Mercy Watts Short) The Wife of Riley (Mercy Watts Mysteries Book 6)

The Wife of Riley (Mercy Watts Mysteries Book 6) A Good Man Gone (Mercy Watts Mysteries)

A Good Man Gone (Mercy Watts Mysteries) The Wife of Riley

The Wife of Riley A Fairy's Guide to Disaster

A Fairy's Guide to Disaster Coke with a Twist (A Mercy Watts short)

Coke with a Twist (A Mercy Watts short) Dry Spell: A Mercy Watts Short

Dry Spell: A Mercy Watts Short