- Home

- A W Hartoin

Down and Dirty (Mercy Watts Mysteries Book 9) Page 3

Down and Dirty (Mercy Watts Mysteries Book 9) Read online

Page 3

Then, because of who Dad was and how he was, Mom got attacked, nearly raped, and had a stroke. She was doing great, better than we could’ve hoped for really, but Dad couldn’t get past it. It was like every stress and anxiety that he refused to feel for the last thirty years hit him all at once when he saw my mom lying in a hospital bed. He’d left her alone and she paid for his career. Now he couldn’t stand to be away from her for more than ten minutes. I didn’t get what was happening. It was almost like a kind of phobia and it was straight up driving Mom nuts. “Are you coming?” asked Claire.

“How about I find Mom and bring her back?”

“She won’t be happy.”

It was the Kobayashi Maru: parents edition. I couldn’t win unless I pulled a Kirk and reprogrammed somebody. It had to be Dad, but nobody told him what to do. If anything, the crazy made him more difficult.

“I’ll think of something,” I said.

“Mercy?”

Oh, no. Not the tone. Anything but the tone.

“Yeah?” I ask hesitantly.

“I think I need a vacation.”

Crap on a cracker.

“When?”

“Um…well…”

That meant yesterday. Not that I blamed her. Working for Dad was high speed, low drag at the best of times. Now it was ridiculous. In addition to Dad being out of commission, the best detective in his stable, Denny Elliot, got murdered in our backyard during Mom’s attack. The case made the news world wide and Dad was more famous than ever, having been profiled on every show from Dateline to The Today Show. He was a cartoon character on The Simpsons, for crying out loud. Business was booming, but there weren’t enough people to boom it with.

Claire, also, had the misfortune of showing up at the house seconds after Valentina Dwyer shot Mom’s attacker on the stairs. She’d seen Scott Frame’s body and the gore. I was a nurse. It wasn’t new to me, but Claire was a secretary. She had to go on Ambien to sleep more than fifteen minutes at a time.

“I get it,” I said, trying my best to not sound irritated, which I was, but I had just enough energy to know that wasn’t fair to Claire.

“Do you?” she asked.

“Yeah, but can we talk about that later?”

“When?”

“Soon.”

“I’m serious, Mercy. I really have to go…somewhere.”

“I totally understand, but I have to find my mom. Did she take the car?”

Please say no.

“No.”

Thank God.

“She’s probably at The Girls,” I said.

“I called over there,” said Claire. “But no one answered.”

“They’re in California visiting Lawton and the staff is either with them or on vacation.”

Claire’s voice went high and tight. “Then she wouldn’t go there.”

“That’s exactly where she’d go.”

I parked in front of the Bled Mansion a half hour later. The chocolate had worn off and exhaustion had gone bone deep. I dragged myself out of my truck and leaned on the big wrought-iron gate as I keyed in my security code. There was a loud click and I let myself in. Usually, I loved going over to my godmothers’ house. The Bled Mansion was a second home. I’d been born there and was practically raised in the grand art deco mansion that some called a monstrosity or at the very least bizarre. I thought it was beautiful and unique with its huge conservatories on either side in all original glass with ironwork that suggested Egyptian hieroglyphics holding it up. The house itself was pale grey stucco and had bloated green marble columns across the front. None of the windows matched, but there was a kind of symmetry to the asymmetry.

Right now, all the shades were drawn and the lights were off. Myrtle and Millicent would be gone for another week or two. Only a gardening service would be around to make sure the large yards stayed up to standard on snotty Hawthorne Avenue. My parents’ house was down the street in a more modest Bled house built by Josiah Bled and given to my mother after the old man disappeared under mysterious circumstances that I hadn’t been able to figure out. Yet.

I trotted up the marble steps to the oversized front door and keyed in my door code. The decorative iron door slid out of the way into the wall and I opened the regular door to peek inside. I didn’t like going there when The Girls were traveling. All the furniture was covered with white sheets and it felt like there had been a death in the family.

“Mom!” I called out and my voice bounced around the super high walls, giving me the creeps.

Nothing. I had to go in and I did, reluctantly going through the rooms one-by-one. Mom was there, for certain. The kettle on the stove was still hot and there was a tea wrapper lying on the counter. Mom wouldn’t leave a mess and go somewhere else.

“Mom! Come on! It’s been a rotten day! Did you see the news? I smell like a sludge tank!”

Nothing, so I went up the curving grand staircase and that’s when I got the feeling. Not the something isn’t right feeling, the holy crap something’s going to happen feeling.

“Mom! You’re freaking me out!” I went straight to her room. The afghan Millicent had made her was in a rumpled-up ball, but no tea cup. I stood with my hand on the beautifully carved mahogany footboard and knew exactly where she was. My room. I didn’t lock my door. Why didn’t I lock my door?

I ran down the hall and flung it open. There she was, sitting on the bed with Stella Bled Lawrence’s book open on her lap. The Girls had given me the book in August when they realized that I’d been researching The Klinefeld Group in an attempt to find out why they’d come after the Bleds and my family. Stella had sent something back from Paris with my great great grandparents, Amelie and Paul, and The Klinefeld Group wanted it so bad they were willing to kill for it and had. Three times.

“I wondered how long it would take for you to show up,” she said mildly.

I couldn’t speak. I would say that my heart was in my throat, but I think everything was in there. Kidneys, liver, all my innards jammed into my throat. That I was able to breathe was a miracle.

“Interesting little project you’ve got here.” Mom glanced around the room pointedly. My boyfriend, Chuck, and I had put up corkboards on easels. I’d been working my way through Stella’s book, trying to figure out what exactly she’d been up to during WWII and where. I had a European map with pushpins marking the places I knew Stella had been. Other boards had mind maps on them, zigzagging connections between people and events that covered decades and generations.

Think of an explanation. Something good.

“I didn’t do it.”

That’s not good. What are you? Five.

“I’m sorry,” I said.

Better.

Mom pursed her lips and attempted to shift them sideways. It didn’t quite work. The stroke had affected her face and no amount of therapy seemed to make much difference. “Tell me what you’re sorry for.”

“I don’t know.”

Holy crap. I am five.

“I didn’t mean for you to find this.”

Dammit.

“Never mind.” I flung myself on the bed and after a minute, Mom rubbed my back. I didn’t look up. I couldn’t face it. Chuck and I had been working on The Klinefeld Group for so long and I had so many questions. Questions that I was afraid to ask.

“Mercy?” said Mom with a slight slur. “Why do you have Stella’s book? What is this map about? Who are these people?”

I made myself sit up and face the music, crisscross applesauce, as all good five-year-olds do. “We’re tracing Stella.”

“Why?”

Just say it. She already knows. She has to.

“Because The Klinefeld Group isn’t going away,” I said.

Mom leaned back on the pillows and picked up her favorite teacup, the one I picked out for her in Paris when I was ten. It had pink Eiffel Towers and yellow croissants. “What do you know about them?

“Less than you.”

“I don’t think so.”

/>

Mom let me question her. I couldn’t believe it. She’d always been evasive at best when it came to us and the Bleds. Mom said she didn’t know what The Klinefeld Group was after. Her parents, Nana and Pop Pop, didn’t know either. Mom confirmed what The Girls had told me. Nobody in the family knew either.

“What about Agatha and Daniel?”

Mom looked down into her cup, her large green eyes filling to the brim but not going over. Agatha and Daniel were her grandparents. They were killed in a plane crash when she was a teenager. It was not an accident.

“Mom, I’m not trying to upset you,” I said. “But I’m not giving up on this and neither is The Klinefeld Group.”

“You should leave well enough alone.” She was so quiet. I could barely hear her.

“I can’t because it’s not well enough. The Girls agree with me. You can ask them.”

Mom ran her fingers over Stella’s book opened to a particularly perplexing page, several letters written to The Girls’ mother, Florence, in code. I couldn’t make anything out of it and neither could Chuck. Stella didn’t use any easily deciphered code. Of course, she wouldn’t. She was a spy, but it appeared that Florence understood it. She’d made little blue hashmarks on the letters. Florence was no spy. She was an elegant society lady with no connections to the military or covert operations.

“They let you have the book,” said Mom. “I didn’t imagine I’d ever read it, much less you.”

“They want to know what was worth killing for.”

Mom pulled up my crocheted coverlet and the left side of her face sagged more prominently. “Poor Lester. Wrong place at the wrong time.”

“What about Agatha and Daniel? Were they at the wrong place?”

“That was an accident.”

I crossed my arms.

“What is with you people?”

Mom’s eyes widened. “You people? Since when are we you people?”

“Since you don’t tell me the truth.”

Mom yawned and her eyes flitted over to the map. “I don’t know what the truth is.”

“What about Dad?” I asked.

“Dad?” she scoffed. “Your father doesn’t know what they want and he doesn’t know who they are.”

“Did he try to find out?”

“No.”

“Why the hell not?”

“Mercy!”

“Hello, Mom. World-famous detective doesn’t look into the murder of his wife’s grandparents? Puhlease.”

“He didn’t.”

“Why not?”

“It was a long time ago.”

“Lester wasn’t.”

Mom sipped her tea and a dribble of liquid slipped down her chin. I rushed to get her a tissue, but she wiped it away with the back of her hand in frustration. “I know when Lester died. I think about him all the time.”

“You do?”

“Of course. I don’t understand why they came back. It was quiet for so long and then…”

I bit my lip. I couldn’t bring myself to tell her that it was my fault. Me on the news. The Klinefeld Group noticed my connection to the Bleds and back they came. I got a lot of attention and Mom hated it. She always kept her head down and she couldn’t understand why I didn’t, as if I had a choice. Stuff happened and it usually happened to me.

“I don’t suppose we’ll ever know why,” she said. “We’ll never know why they went after Agatha and Daniel when they did.”

“I know why.” It just slipped out. I can never just shut up.

Mom reached out to me with her bad hand. The fingers still didn’t work quite right and I could see it in the stretch. I took it and pressed her hand between mine, wishing I could change it, knowing that some things never change.

“You couldn’t possibly know,” Mom said, her eyes sad and resigned. “You’d be guessing.”

I decided to take that look away. Mom needed something and it sure as hell wasn’t Dad freaking out. “I know exactly what happened.”

Her face lit up the way I hoped it would and I told her about Dr. Bloom, the Oxford professor, his interview with the Paris antique shop owner, and the theft of his research shortly before Agatha and Daniel were murdered.

“He’s pretty torn up about it,” I said.

“That poor man. It’s not his fault.” Mom tried to roll her cup between her hands, but couldn’t manage it. “So you’ve been busy and there are other people involved.”

“I have and there are.”

“And you’ve been hiding it from us.”

“Are you the pot or the kettle in this scenario?” I asked with a grin.

“I, in no way, resemble cookware of any kind.”

I rolled my eyes.

“So what else have you gotten your little nose into?”

I thought about lying, an instinct when it came to my parents, but I told her the truth. It surprised her and it sure as the heck surprised me. I blame it on exhaustion.

I told Mom that it all started with Brooks’ lawsuit and the Art museum’s attempt to get ahold of The Bled Collection. I had no idea that it would take me to a policeman’s murder in Berlin, an abandoned apartment in Paris, and my own great grandparents’ murders well before I was born. Now I had to know what happened and why. I couldn’t walk away even if The Klinefeld Group did. No way. Not gonna happen.

Mom yawned and closed her eyes. I caught the tea cup before it spilled. “Mom, I’ve got to take you home.”

“I have to sleep.”

“But Dad—”

“He has to deal sooner or later. I’ll stay here.” She slipped down and took a deep breath.

I pulled the coverlet up over her shoulders. “On one condition.”

“What’s that?”

“I want to know why Dad didn’t investigate Agatha and Daniel.”

“Because I asked him not to.”

Chapter Three

I COULD’VE WALKED down the street to my parents’ house, but that would’ve meant walking back. I wasn’t sure I could make it so I drove down and parked in front under the oak tree. Its leaves were a brilliant reddish-yellow and they were falling gently down so perfectly it looked like they were on a timer. The yard was completely covered, giving me pangs of childhood pleasures. Despite growing up on Hawthorne Avenue, my family was decidedly down market. Dad was a cop and Mom a paralegal. There wasn’t much money and Mom was a huge fan of free. Leaves were free and fun. We’d rake them into huge piles and dive in headfirst, making a huge show of ourselves on the sedate avenue. People used to draw their curtains when we got going. October was always my favorite month. Mom’s, too. I think as much as she loved our neighbors, the prudishness notwithstanding, she liked bothering them, too. She was always doing things that weren’t done on our street like letting me carve the pumpkins. I was terrible at it and nobody else put out real pumpkins anyway. They had porcelain pumpkins made by Lennox or Wedgwood. Mom bought our decorations at yard sales so nothing matched and all of it well-worn. The avenue didn’t like it. Halloween was a particular bone of contention. Nobody dared say anything to us because of Millicent and Myrtle. I did hear the whispering. Sometimes I think whispering is meant to be heard. There certainly was a lot of it. When I was six, I heard a couple of neighbors at Straub’s grocery asking each other why we were on the avenue. “What were we doing there really?” “It was quite ridiculous.” “Why I never in all my life blah blah blah.” That was the first time I realized we were different and it mattered. I told Mom and she said it didn’t matter. It was our house so we belonged. End of story. Except it wasn’t.

What happened to Josiah Bled? Why did we get his house? I wanted Mom to tell me why my life happened the way it happened, but I had a feeling that she wouldn’t because she couldn’t any more than The Girls could tell me what The Klinefeld Group wanted. Somebody knew and that somebody might be my dad. He was the last one to see Josiah Bled. They flew together to Paris where they took a train to tiny Hallstatt, Austria. Dad came back, but Josiah was nev

er seen again. When I thought about it, I got a knot of wiggling fear in my gut. I didn’t think Dad did something to Josiah exactly, but something happened in Hallstatt.

I walked up the brick walk kicking the leaves and looking at the porch where normally Mom’s ragtag bunch of ghosts, goblins, and witches would be. She wasn’t allowed to drive or climb ladders so they remained tucked away in the attic. Dad should’ve thought to get them out for her and put them up. But he didn’t. He probably never noticed that she decorated. He didn’t notice a lot of things so I’d do it and I might even get a few extras to annoy the neighbors.

The porch creaked as I walked across, knocked, and let myself in. Now under Dad’s new paranoia plan I had two codes and a voice recognition sentence to get into my parents’ house. It was annoying and probably unnecessary. Dad kept pointing out that he’d pissed off a lot of people and not all of them were in prison. I wished he’d shut up about that. It didn’t help Mom to remember there might be more guys out there waiting to take revenge. Once again, he didn’t notice. Dad said he’d changed, but in a lot of ways he hadn’t.

“Mercy!” called out Claire. “Is that you?”

“Yeah. I found Mom. She’s snoozing at The Girls.”

Claire came bounding down the stairs, neatly jumping over the spot where Scott Frame died. I’d expected her to get over that aversion, but she hadn’t so far.

“Thank goodness. Tommy was about to have kittens,” she said, smoothing her perfect blond hair. Claire’s hair obeyed. It was sleek and shiny, refusing to tangle. My hair tangled like it was in its job description.

“Where is he?” I asked, trying to do a finger comb and getting my hand stuck at the scalp.

“Upstairs. Big Steve’s here and he’s distracted.”

We walked back into the kitchen and I got a little chill. For some reason, I always looked for Mom’s shoes. She’d been barefoot during the attack and that small fact clued me in to what really happened outside. The shoes weren’t there, but I walked in, feeling like no time had passed, not a day, not an hour.

A Monster's Paradise (Away From Whipplethorn Book Three)

A Monster's Paradise (Away From Whipplethorn Book Three) A Sin and a Shame (A Mercy Watts Short)

A Sin and a Shame (A Mercy Watts Short) Fierce Creatures (Away From Whipplethorn Book Two)

Fierce Creatures (Away From Whipplethorn Book Two) Strangers in Venice

Strangers in Venice Mean Evergreen (Mercy Watts Mysteries Book Twelve)

Mean Evergreen (Mercy Watts Mysteries Book Twelve) Down and Dirty (Mercy Watts Mysteries Book 9)

Down and Dirty (Mercy Watts Mysteries Book 9) Small Time Crime (Mercy Watts Mysteries Book 10)

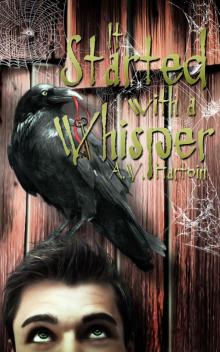

Small Time Crime (Mercy Watts Mysteries Book 10) It Started with a Whisper

It Started with a Whisper My Bad Grandad

My Bad Grandad A.W. Hartoin - Mercy Watts 04 - Drop Dead Red

A.W. Hartoin - Mercy Watts 04 - Drop Dead Red Brain Trust

Brain Trust In the Worst Way (Mercy Watts Mysteries Book 5)

In the Worst Way (Mercy Watts Mysteries Book 5) Diver Down (Mercy Watts Mysteries)

Diver Down (Mercy Watts Mysteries) Nowhere Fast (A Mercy Watts Short)

Nowhere Fast (A Mercy Watts Short) Touch and Go (A Mercy Watts Short)

Touch and Go (A Mercy Watts Short) The Wife of Riley (Mercy Watts Mysteries Book 6)

The Wife of Riley (Mercy Watts Mysteries Book 6) A Good Man Gone (Mercy Watts Mysteries)

A Good Man Gone (Mercy Watts Mysteries) The Wife of Riley

The Wife of Riley A Fairy's Guide to Disaster

A Fairy's Guide to Disaster Coke with a Twist (A Mercy Watts short)

Coke with a Twist (A Mercy Watts short) Dry Spell: A Mercy Watts Short

Dry Spell: A Mercy Watts Short