- Home

- A W Hartoin

Small Time Crime (Mercy Watts Mysteries Book 10) Page 7

Small Time Crime (Mercy Watts Mysteries Book 10) Read online

Page 7

“You go to the office,” I said. “I’m going home to contemplate the error of my ways.”

“Excellent. Then I will see you on Thursday.”

“Not that error. It’s not an error.”

She got squinty. “What error then?”

“Getting up this morning and thinking something could possibly go right for me,” I said.

“Don’t exaggerate,” she said. “You were always dramatic, even as a child.”

“Oh, yeah? Because you refused to identify your friend’s medal, I got strip-searched by Patricia and Eloise at the airport and they are not nearly as gentle as they sound. Strip-searched. Naked.”

“Mercy, please,” said Aunt Miriam. “This is a medical facility. People are ill.”

“Yeah, me. I’m sick and tired and I want to go to Greece and have umbrella drinks for free.” I whipped open the door to the stairs and tossed her cane down the hall. “Do not call me unless you want to help me.”

“I need you to come to the doctor,” she said.

“For what?”

“You’re a nurse.”

“I’m not a mind reader.”

“I’m family.”

“Great,” I said. “If family is what you require, I’ll call the family. How about my mother? She’s almost got the drooling under control. Or my dad. No? You don’t want to take my dad to the gyno. How about this? I’ll call your brother. Grandad surely wants to sit in an office with Dr. Harrison and think about what all those speculums do.”

“You wouldn’t,” she said, blushing more red than her hair.

“Before today? No. Absolutely not. After Patricia and Eloise? You bet.” I went into the stairwell and ran down the stairs. I did not have on the right bra for that and it hurt, but I didn’t care.

“Mercy! Mercy!” There was a pleading to Aunt Miriam’s voice and Dr. Harrison said there was something wrong. She was old and family and old.

I stopped. “What?”

“Mrs. Haas called. You have to go take down your mother’s Halloween decor. Tommy didn’t do it.”

I am so over family.

CHAPTER FIVE

FAMILY WAS NOT over me. I smelled the family stink from the hallway outside my apartment. It was oily, fatty, and heavy with despair. Uncle Morty was in there, cooking up kielbasa and sauerkraut. Why he had to do it in my apartment was anybody’s guess. I couldn’t face it. I really couldn’t.

Luckily, I knew someone who could. I pulled out my phone and Mr. Cervantes stuck his head out in the hallway. “Mercy, I think Morty’s in there. It really smells.”

“I’m on it,” I said, dialing.

“Why didn’t you go to Greece?”

“You don’t want to know.”

He paused for a second and then said, “I believe you.”

The phone was ringing and I waited while giving Mr. Cervantes a thumbs-up so he’d trust me and go back into his apartment where it smelled nice.

“Huh?” my friend and occasional sidekick, Aaron, answered.

“I need help. We didn’t go to Greece and Morty is making that cheap kielbasa in my apartment. It’s the kind where you can see the veins and comes with snout hairs.”

No answer. Typical. Aaron was not a talker unless he was talking about hotdogs or Star Trek. Sci-fi is big in my life and his, since he owns a Star Trek-themed restaurant, Kronos, and just opened a Klingon-themed bakery, Sto-Vo-Kor.

“Aaron?”

He hung up. Also, typical. I figured it would take the little guy about fifteen minutes to get whatever cooking supplies he needed from Kronos and hoof it over. I could either go in, absorb that smell, and actually stink the way people thought I did, or I could go put away Mom’s Halloween stuff. Dad had promised he’d do it, since Mom couldn’t climb a ladder and was opposed to paying anyone to do it, like everyone else on the block did. I knew very well I was going to have to do it. I’d just been putting it off. If Mom came back from Cairngorms Castle with a skeleton still up in time for Thanksgiving, she would climb a ladder. That could not happen and Dad’s new leaf wasn’t completely turned over, no matter what he said.

I borrowed a pair of running shoes from Mr. Cervantes so my feet wouldn’t freeze and went slowly down the stairs. No jogging. My chest hurt bad enough already and I had to admit it felt nice outside. The snow had stopped, leaving everything sparkly with a light frosting and when I got to my parent’s street, I realized how far behind we were. All the mansions were done up with stalks of corn, professionally carved Thanksgiving-themed pumpkins, and the occasional pilgrim diorama. I particularly liked the McCallisters’ where all the pumpkins were Lenox porcelain and cream-colored, for some reason.

I grew up on the avenue, so you’d think I’d understand them, but I didn’t. My family didn’t have china and I carved the pumpkins, badly. Mom didn’t believe in fancy pumpkins that the parents bought or carved themselves, although that was the fashion, especially after Pinterest started. Moms were all about the Pinterest and perfection. My mother couldn’t be bothered. She bought a pumpkin that was so misshapen that she got it cheap and then handed me a dull steak knife. I went to town, doing some seriously bad artwork that she invariably loved. I think she didn’t do as the others did because she was perfect herself and didn’t need to prove anything with a flipping pumpkin, not that she said she was perfect. It was just one of those things. I never met anyone who didn’t love my mom. She was just her and that was enough. Not something I inherited. I got the face and bod, none of the charm or elegance. What a rip-off.

When I stopped at our house, I have to say Mrs. Haas was right. Our house was bad. I’d done my usual stellar carving job on three pumpkins that were ugly to start. Now they were sunk in and rotting with some ooze running down the front steps. Our bedraggled skeleton that Mom got at a yard sale when I was five had lost a foot, both hands, and, most importantly, his head. Our house was a three-story Tudor, designed by Josiah Bled, so it came with a built-in creepiness, even more than the other mansions on the street. They all had a not-really-lived-in quality that lent credence to the ghost stories that went around and were now part of the history of St. Louis. Our house was supposed to have the ghost of Bernice Collins. She was Josiah Bled’s mistress and she disappeared. It was generally thought that he killed her in the butler’s pantry. It was abnormally cold, for no good reason, but I’d never seen her or any other ghost on Hawthorne Avenue.

I’d have to get out the ladder and climb up to cut the wires Dad used to hang that skeleton. There was no way I could undo the wires with my arm in a cast. I wasn’t even sure I could carry the ladder, but I managed it, mostly by dragging it and cursing. My phone started going off with my mom’s ringtone, “Survivor” from Destiny’s Child.

I answered without thinking twice. There wasn’t any mistake I wouldn’t make that day. “Hi, Mom.”

“Why’d they bring you in?” Dad whispered.

“Ah, crap.”

“Quick. Tell me. I don’t have much time.”

I leaned against the tree and swatted the skeleton’s remaining foot out of my face. “Very cloak and dagger, Dad. What’s up?”

“It’s cloak and your mother. She’ll be back from her high tea any second. Why did those morons haul you into the Federal building?”

“Did Morty call you? Don’t tell Mom. She’ll get upset.”

“I’m not telling her anything and that bastard didn’t tell me. I know people.”

“Who do you know?”

“Focus, Mercy. What did you do?” asked Dad.

“Nothing. Not a thing.”

“Why are you on the No Fly List?”

I groaned and hauled the ladder upright. “‘Cause they’re pissed and they want me to do something that I’m not going to do.”

“Do it,” he hissed. “Do it now. Today. Yesterday, if possible.”

“Are you smoking crack? You don’t even know what it is.”

“I know that business has gone down sixty-two and a quarter perc

ent since they cut ties with me and announced that I’m an unreliable dipshit.”

“They never called you a dipshit.” I was smiling. I couldn’t help it. Usually, it was me under fire. Totally Dad’s turn.

“Can you not hear me? Sixty-two and a quarter percent downturn.”

“That’s a lot.”

“You’re goddamn right it is. Now do what they want, but make sure bringing me back on is part of the deal.”

“Dad, I’ve got to get a skeleton out of a tree right now, so this will have to wait.”

“What skeleton?” he asked. “Is that part of the case?”

“It’s part of pissing me off. You didn’t take down the Halloween decor like you promised.”

“Nobody cares about that.”

“Incorrect. You don’t care. But Mom cares. I care. The avenue cares,” I said.

“It’s not important. Oh, shit. I think that’s her,” said Dad. “Get me back in. I need back in.”

I started climbing the ladder. Such a bad idea. It was unstable at best, kinda like me. “They’re total dirtbags, Dad. Look what they did to you and Mom.”

“Mom understands,” he said.

“She prays they get herpes. All of them. The whole FBI.”

“Oh, good. It wasn’t her,” he said. “Okay. Do we have a deal?”

I got to the top of the ladder and eyed the wire. It was pretty far. I might have to get Chuck. “No.”

“Mercy, it’s for the family.”

“It’s for you.”

“The business is a family business.”

“Whatever.”

“Mercy.” Dad’s voice turned sweet and pleading. “I need this and make no mistake, your mother does, too. What are we without the business?”

“A happy couple?”

“We are happy. I’m here on vacation, not drumming up business. I got a pedicure today. A pedicure!”

“Dad, as much as I enjoy saying no, I’m not just messing with you. I already tried to do what they wanted and it’s a no-go.” I told him about Sister Margaret and Aunt Miriam. I finished up with our delightful trip to the gyno. That alone almost made him choke on his tongue.

“Don’t say anymore,” he said.

“The doc wants to do an exam.”

“Girl, if you don’t shut up about that I’ll—”

I laughed. “Come home and deal with it yourself? I dare you to try it. You horned your way into that vacation. You can’t just ditch them when you find something better to do. That’s the old you.”

“Help them, Mercy,” he said, pulling out the charming voice that was so rarely used with me. “It’s the right thing and you know it.”

“You want me to help the FBI. That’s who you want to help?”

“Yes, and don’t be difficult about it.”

“Dad, if I ever do anything to help anyone ever again, rest assured it won’t be for the FBI. Kent Blankenship bit my face because of those crapbags. I wouldn’t help them to the toilet if they had amoebic dysentery.”

“Mercy, as usual, you misunder—”

I hung up and flung my phone across the yard into a pile of leaves. So satisfying. You have to try it.

I turned my attention to the skeleton, holding onto the ladder with my bad hand, mostly fingertips, and reached out with the wire cutters.

Just another inch. Almost there. Shift a little. Lean. You won’t have to ask Chuck to do it, like a wussy short person. You can do it.

“Mercy!”

I fell so fast I don’t remember it happening. I remember lying on the ground, unable to breathe and mentally cursing my father. Myrtle and Millicent, my Bled Godmothers, bent over me, their gentle faces wreathed in fear.

“Are you alright, dear?” asked Millicent.

“Can you breathe?” asked Myrtle.

They asked a lot of questions. I didn’t answer a single one, but it wasn’t really necessary. They talked enough for the three of us and examined me for a blow to the head, which they were sure I had, otherwise why would I ever climb a ladder in my condition. In their world, a broken arm was a good reason to take to your bed for at least a month, not that they would do that. For little old ladies that looked as delicate as Murano glass, they were surprisingly tough.

Millicent got me upright by threatening to call 911 and then checked me for broken bones. New broken bones.

“She seems fine,” said Myrtle.

“This isn’t normal. Look at her eyes,” said Millicent.

“What’s wrong with my eyes?” I asked.

They threw up their hands and hugged me as I struggled to my feet. Apparently, I had circles under my eyes in addition to my presumed head injury. I tried to explain about Mrs. Haas, but they weren’t having it.

“That is ludicrous, Mercy,” said Myrtle. “You’re already injured. How does your arm feel?”

Hurts like hell.

“Fine. The same.”

Millicent picked leaves and twigs out of my hair and Myrtle tried to pull down the ladder until I put a stop to that. “I need that up.”

“You certainly do not. We will have a service to it,” said Millicent.

“You know how Mom feels about paying for things that we can do ourselves.”

“We’ll pay for it,” said Myrtle.

“That still counts and it’s not your problem.”

They watched me, calculating their next move and straightening their tartan wool trousers and the short capes they wore over their silk blouses. They didn’t match but they went together, like they had all their lives.

“We’ll ask Chuck to do it,” said Millicent with a decided air.

“It’s not his problem,” I said.

“That’s what men are for,” said Myrtle, pulling me away from the ladder.

“Lawn care?”

“Among other things. He’ll want to help.”

“I don’t know about that.” I dug my phone out of the pile and turned it off, ignoring the fifty thousand messages from Dad. “Chuck was an apartment kid. I don’t think he speaks lawn care.”

“He’ll learn.” Millicent eyed me putting my phone in my back pocket. “I assume that was Tommy.”

“You assume right.” I took them onto the front porch and settled them in the cushy chairs with lap blankets while I threw away the pumpkins and scrubbed off the ooze. They watched, sipping chamomile tea, but they weren’t happy about it. The Girls often wanted to help us, especially Mom and even more especially after the stroke, but Mom wouldn’t go for it. The Girls had given us our house for reasons I hadn’t put my finger on yet and paid for my pricey education. Mom said that was more than enough. It wasn’t enough for me. I wanted to know why they gave us what they gave us, but that information wasn’t forthcoming, so I was determined to figure it out on my own.

“Do not go back up that ladder,” warned Millicent. “I don’t care what Tommy says. For a brilliant man, he hasn’t an ounce of sense when it comes to you.”

“Dad doesn’t care about the skeleton or any of this stuff. He’s just hassling me as usual,” I said, pouring the hot soapy water down the stairs.

The Girls frowned in unison.

“It’s not a big deal,” I said. “He wants back on the FBI payroll and he thinks I can help him.”

“Surely not?” said Myrtle aghast. “After how they treated your mother?”

“Yep. You know him, all about the business.”

“I don’t understand it,” said Millicent. “He loves your mother so.”

I shook my scrub brush off and stretched my back until it popped. “He loves work, too, and the FBI has cachet that he can’t get anywhere else.”

Millicent swirled her tea and asked, “Why does he think you can help? You’ve been rather hostile to them.”

“They want a favor. He thinks I should do it.” I sat down at their feet like I did when I was little, looking up into their kind faces and feeling safe and warm no matter the temperature.

“Is it about that place

in Kansas and that horrible man?” asked Myrtle.

I frowned. “What man?”

She touched her lip. “The one that bit you.”

“Oh, him. No, nothing to do with Blankenship, but it is to do with Kansas,” I said.

“About your mother’s case then? Or one of your other cases?”

I laughed and put my head on Myrtle’s warm knee. “No. Nothing to do with me at all.”

“Then why are they coming to you?” asked Millicent.

I didn’t want to answer. A murdered nun. No good could come from talking about that. “What are you guys doing out here anyway? You didn’t just happen by.”

“We saw you pass and wanted to talk to you about something,” said Myrtle.

“What?” I asked.

“Don’t let her change the subject,” said Millicent. “Why are they coming to you?”

I yawned and closed my eyes as Myrtle stroked my hair. I might as well have been five. It was wonderful. “It’s about Aunt Miriam. But it happened a million years ago. They want her to talk. She won’t talk. You know how difficult she is.”

The Girls were quiet and I started to get a feeling, a sinking, this-is-about-to-be-a-pain-in-your-ass kind of feeling, but I said nothing. I had enough pain. I was full up on pain.

“A case?” asked Millicent after a few minutes.

“Sort of. It’s solved, so nothing dramatic,” I said. “You should go home. I think the temperature is dropping and those capes aren’t enough.”

“Was it a murder case?” Myrtle stopped stoking my hair and she was gripping it so tight it almost hurt.

“Yes,” I said, slowly.

“Sister Maggie?”

My stomach flipped and I looked up. Their faces were pale and their cups shook slightly. I gently took the cups and put them on the side table. Millicent looked away and Myrtle put her hand over her mouth.

“Is Sister Margaret Mullanphy Sister Maggie?” I asked.

Myrtle nodded.

“Did you know her?”

“Very well.”

“I’m sorry. I didn’t know that.”

Millicent turned to look at me like she’d never looked at me in my whole life. Her eyes flashed and her soft, cultured voice was hard and accusing, “Tell us what happened.”

A Monster's Paradise (Away From Whipplethorn Book Three)

A Monster's Paradise (Away From Whipplethorn Book Three) A Sin and a Shame (A Mercy Watts Short)

A Sin and a Shame (A Mercy Watts Short) Fierce Creatures (Away From Whipplethorn Book Two)

Fierce Creatures (Away From Whipplethorn Book Two) Strangers in Venice

Strangers in Venice Mean Evergreen (Mercy Watts Mysteries Book Twelve)

Mean Evergreen (Mercy Watts Mysteries Book Twelve) Down and Dirty (Mercy Watts Mysteries Book 9)

Down and Dirty (Mercy Watts Mysteries Book 9) Small Time Crime (Mercy Watts Mysteries Book 10)

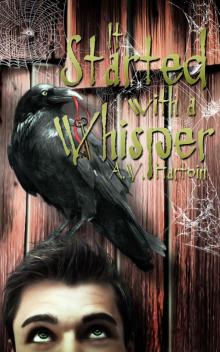

Small Time Crime (Mercy Watts Mysteries Book 10) It Started with a Whisper

It Started with a Whisper My Bad Grandad

My Bad Grandad A.W. Hartoin - Mercy Watts 04 - Drop Dead Red

A.W. Hartoin - Mercy Watts 04 - Drop Dead Red Brain Trust

Brain Trust In the Worst Way (Mercy Watts Mysteries Book 5)

In the Worst Way (Mercy Watts Mysteries Book 5) Diver Down (Mercy Watts Mysteries)

Diver Down (Mercy Watts Mysteries) Nowhere Fast (A Mercy Watts Short)

Nowhere Fast (A Mercy Watts Short) Touch and Go (A Mercy Watts Short)

Touch and Go (A Mercy Watts Short) The Wife of Riley (Mercy Watts Mysteries Book 6)

The Wife of Riley (Mercy Watts Mysteries Book 6) A Good Man Gone (Mercy Watts Mysteries)

A Good Man Gone (Mercy Watts Mysteries) The Wife of Riley

The Wife of Riley A Fairy's Guide to Disaster

A Fairy's Guide to Disaster Coke with a Twist (A Mercy Watts short)

Coke with a Twist (A Mercy Watts short) Dry Spell: A Mercy Watts Short

Dry Spell: A Mercy Watts Short